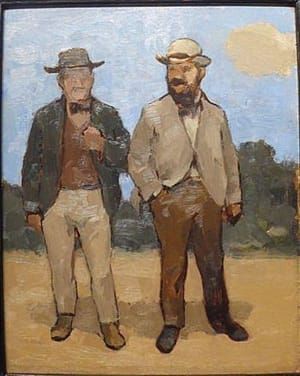

Late Afternoon, 1964

Albert York

York's figures often seem eccentrically posed, and yet the way the curve of a knee echoes the hollow of a dog's throat lends one bucolic scene a magisterial expansion, something akin to continental drift wrenching South America out of Africa. (http://www.villagevoice.com/arts/painters-paradise-batting-750-on-the-upper-east-side-7180310)

(http://www.sienese-shredder.com/2/william_corbett-albert_yorks_art.html)

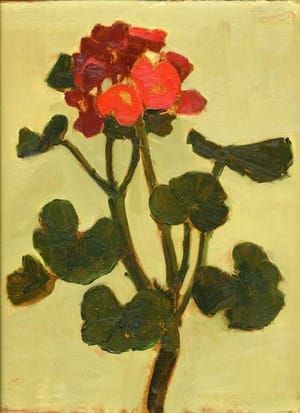

...The current display has 24 works dating from 1963 to 1990—a brutal perfectionist, Mr. York never finished a painting after 1992, and he is believed to have completed only about 250 during his lifetime. (A catalogue raisonné is being produced, which should sort this out and become an instant classic.) While only one work here is larger than a sheet of typing paper, they all deliver enormous visual feasts—made of seemingly simple, halting brushstrokes on board that form powerful, intimate still lifes and landscapes that harbor profound psychological mysteries.

With just a few hard-won marks, Mr. York could render uncanny impressions of the most quotidian subjects: a brown cow in a field, pink flowers in a tin container, a potted plant, a cut lemon that may make your lips pucker. Even up close, there’s no telling how he does it. Those idiosyncratic brushstrokes betray an unmatched willingness to look deeply and continuously and to set aside conventional notions of how objects are supposed to exist in the world.

Albert York, 'Late Afternoon,' 1964. (Courtesy Davis & Langdale)

Albert York, ‘Late Afternoon,’ 1964. (Courtesy Davis & Langdale)

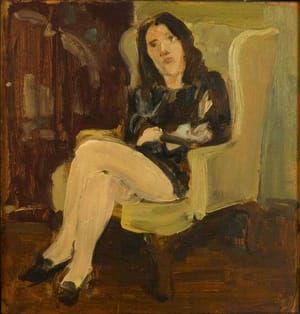

Frequently this takes the form of an emotionally charged voyeurism, sometimes cut through with a kind of quiet, more or less latent surrealism. Private moments are espied in public: two women seated on grass, looking silently off into a blank horizon (only their dog seems to notice us), or a nude woman in front of a tree who examines her face in a mirror as a skeleton speaks with her, in what is arguably Mr. York’s most famous picture, reproduced in Calvin Tomkins’s 1995 profile of him for The New Yorker, the only interview the artist ever gave.

Much has been made of Mr. York’s explanation to Mr. Tomkins of why he painted—that the world we live in is “a Garden of Eden,” that “it might be the only paradise we ever know, and it’s just so beautiful.” How could you not want to paint it? There is a perfect and blissful kind of raw beauty in his paintings, but what makes them so enduringly haunting is that, as in Eden, there is always a reminder of evil lurking, a potential for a reversal, a downfall. A snake glides through a forest in one, men in Oriental garb stand in brown field, one holding a sword, in another. Eras collapse in on themselves, Eden and East Hampton coeval, at least for one moment; Mr. York had a habit of not always painting quite to the edge of his boards, of leaving a bit of his support peeking through, which makes this effect all the more fragile, as if the whole scene could disappear in an instant.

Mr. York, though, is here to stay. He should not be thought of as one of America’s greatest unknown artists but simply as one of its greats.

(http://observer.com/2013/06/albert-york-a-loan-exhibition-at-davis-langdale-company-inc/)

Uploaded on Apr 20, 2017 by Suzan Hamer

Albert York

artistArthur

coming soon