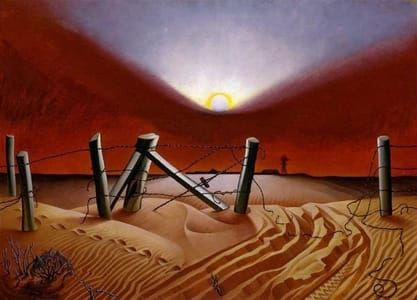

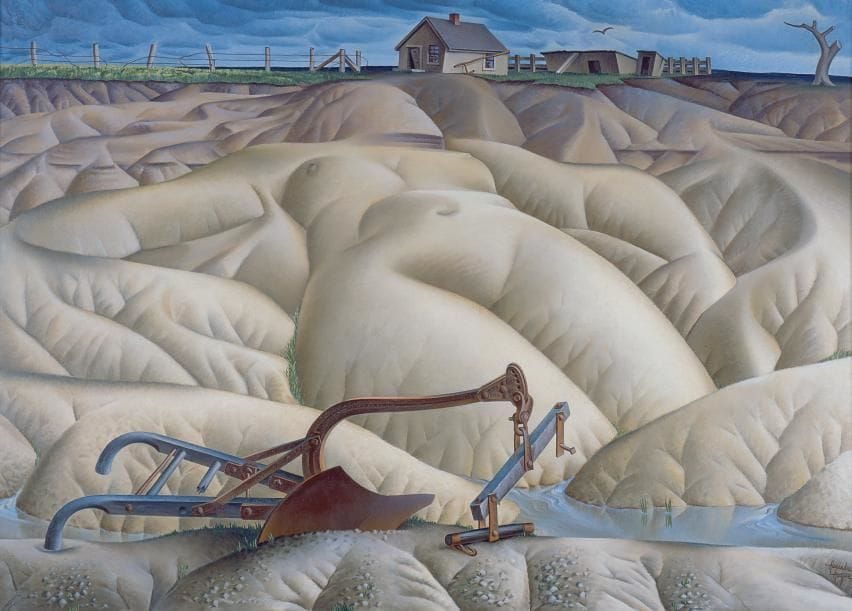

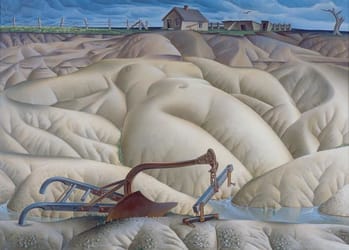

Erosion No 2, Mother Earth Laid Bare, 1936

Alexandre Hogue

American colonialist texts imagined the American prairie and frontier as a virgin or bride, waiting to be conquered and mastered. The American unknown land was also imagined as a benevolent mother, who would welcome heroic pioneers to her nurturing bosom. This imagery changed when colonizers realized how they had “deflowered” the virgin/mother land, how it had become mutilated and deformed. Alexandre Hogue’s painting, “Erosion No 2, Mother Earth Laid Bare” (1936), illustrates this sense of disillusionment and visualizes the metaphorization of the land.

(http://www.obama-institute.com/body-and-metaphor-in-medical-humanities/)

Unlike his peers, Hogue did not sympathize with the plight of America’s farmers. He refused to find heroism in the plight of the homesteaders who clung stubbornly to their land during the “Dirty Thirties.” He saw them as deserving of their fate.

Hogue was right to attribute the Dust Bowl to humanity’s violation of the natural world. Deep plowing of the Great Plains’ virgin topsoil had displaced the region’s native grasses. When drought struck in the 1930s, there was nothing to fasten the soil to the ground. The farmers were truly the agents of their own misfortune.

https://russelltetherfineart.wordpress.com/2014/04/23/introducing-the-art-of-alexandre-hogue/

By representing the land as the body of a female figure, as in 1938’s Mother Earth Laid Bare, Hogue is relating the maltreatment of the land to murder. Mother Earth Laid Bare also presents another disturbing image of land abuse. Clearly, the earth is related to the body of a woman, Mother Earth; the plow becomes a symbol for the rape of the land. The landscape and the woman are both rendered completely barren by the plow. The land is beyond the point of help as water runs off instead of being absorbed. This is a clear statement by Hogue concerning the social context: we have caused the loss of life and we can never return it to its fertility.

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexandre_Hogue)

Uploaded on Sep 30, 2017 by Suzan Hamer

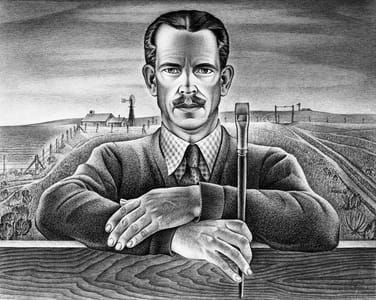

Alexandre Hogue

artistArthur

Wait what?