Untitled, 1973

Alfred Gescheidt

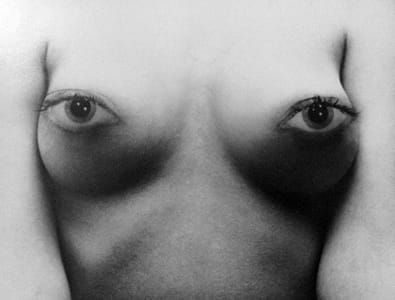

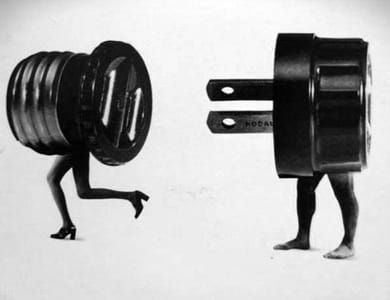

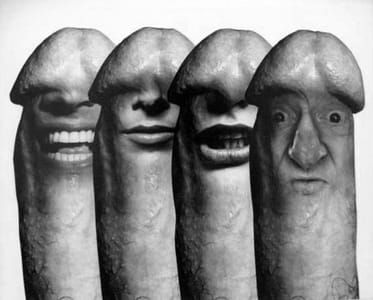

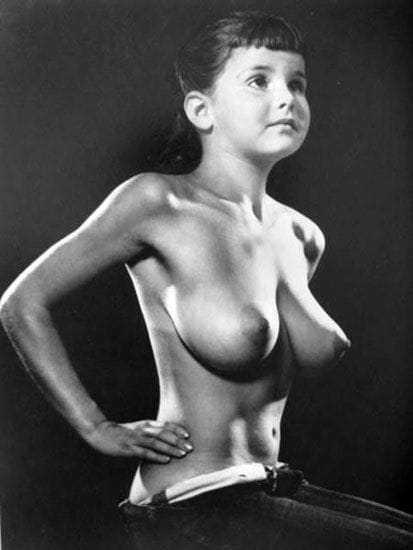

...Gescheidt's overlooked body of work offers a shifting portrait of American anxieties and desires. And it does so most brilliantly in a single series, at the dawn of the sexual revolution. Well before self-avowed feminist art, this male photographer took on the male gaze. It would not have half its comedy or its terror if that gaze were not also a New Yorker's. But then Modernism always knew something about when to step away from reality in the guise of revealing it.

...Gescheidt, who died in 2012, knew fine-art photography as well as anyone. He took to the subways for his first major series in 1951, much as Walker Evans had at least 10 years before him. When he photographed skaters at Wollman Rink in Central Park, in 1965, they seem caught in the stillness of their own long shadows out of Paul Strand. His very vocabulary of black and white, photomontage, and a great deal of sex may make him the last and truest American Surrealist, give or take Llyn Foulkes in California. He looks forward as well. When he shoots the curbs of Manhattan in wild and fragmentary perspective, for the series "Street Cleaner" in 1951, he shares that fascination with what Lee Friedlander was to call "America by Car."

And this is most assuredly postwar America, of men on the subway isolated by light and shadow rather than joined for Evans in the community of the Depression. The Cold War brings irony and dread, from a woman quite literally walking on the head of a pin to a man clinging to the side of a skyscraper. The 1960s loosen up, even as the pressures build. The white shirt and narrow tie give way to the young urban professional—stuck in his own briefcase with a slide rule, too many papers, and "creative department classics." It is increasingly a politically charged and polarized America, of George Wallace and Shirley Chisholm inserted into Grant Wood's American Gothic in 1970, for Politics Makes Strange Bedfellows. Upheaval peeks out through the horseshoe snagging the Washington Monument, with another on its way through the sky.

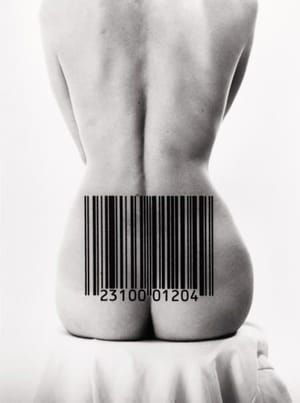

It is an America confused by its own optimism, as for Martin Adolfsson, like a man with a bathing beauty at his fingertips. It is also the America of commercial photography, the business with which Gescheidt supported himself all his life. A snake coming out of a man's fly, its skin all too close in texture to his jeans, could belong to a Levi's ad. No wonder money looms large too, like the long shadow of the words mutual funds. More broadly, the photographs, like a killer ad, aim for that instantly memorable image, centered around a person and a product—only to take on afterward that extra punch of a title. And nowhere does Gescheidt sustain that formula longer or more ingeniously than in Thirty Ways to Stop Smoking.

Quitting time

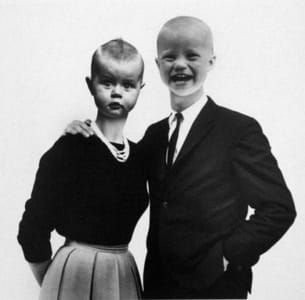

His gallery introduced the photographer in 2009, with work starting in 1949, just when Ionesco was wrapping up his first comedy, La Cantatrice Chauve ("The Bald Soprano"). And no question but Gescheidt's combination of high and low, as well as comedy and terror, was then hitting its stride. Born in 1926, only two years before Andy Warhol, he lived and worked through Pop Art. Still, he hits his stride before Warhol, with deeper connections to the past, and for him popular culture is the medium more than the subject matter. Like advertising, he is representing desire rather than photography....

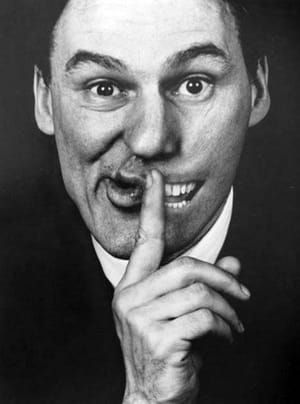

The man comes right out of the theater of the boulevards. Gescheidt needed rediscovery, in part because it took so long for the distinction between high and low culture to crumple, with surely a nod in acknowledgment to him. He also drew on early Modernism, at a time when art, like science, was supposed to march on. He also was more gentle than satirical, when the neo-Pop of the 1980s demanded otherwise. He leaves no doubt about his sympathies, political or otherwise. Yet he always leaves in doubt whether to feel most the comedy or the terror.

Photoshop has made manipulation a way of life, and art has responded by harping on rough edges. Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg insisted on them long ago, long before Warhol's influence or Rauschenberg collaborations came to stand for changes in contemporary art. David Salle and the "Pictures generation" made the edges rougher. Going back further, one could call it a battle between Man Ray and Max Ernst, and Ernst's mad collage has won out. For now, in dreams begin irresponsibilities. Gescheidt's age still dreamed deeply but trusted surfaces.

Gescheidt learned from modern photography's finest artisans of the surface. He studied design, and, yes, his images appeared widely as advertising. They also peer beneath its surface. To this day, their surface looks familiar enough to be worth peeling away. I mistook the woman's slim offer of a cigarette pack for an iPhone. Still, he may depart most from convention as photojournalism—and as a chronicle of a quarter century of desire.

Frustrated desire was at the heart of Gescheidt's special comedy and anxiety all along. The camera's eye is always male, like the photographer himself looking back from a pair of binoculars, but then an anonymous hand grips them both. A drawbridge parts for a nude flat on her back like a barge, while a man treads warily on a carpet of breasts, like walking on eggshells. Another naked man stares up in wonder at an enormous naked crotch, but there is no turning back. He is already well between her legs, without so much as nicotine to calm his nerves. Even without a cigarette, this work smokes.

[http://www.haberarts.com/gescheid.htm]

Uploaded on Jun 20, 2018 by Suzan Hamer

Alfred Gescheidt

artistArthur

Wait what?