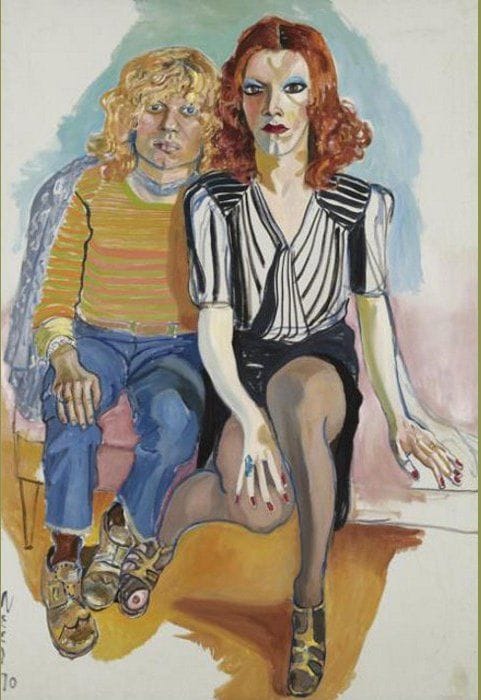

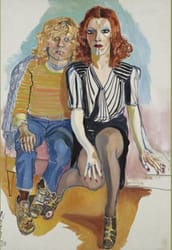

Jackie Curtis and Ritta Redd, 1970

Alice Neel

This bright portrait of two individuals is quizzical and ambiguous. On the left is Ritta Redd, who sits timidly behind the more dominant Jackie Curtis. Redd’s blond curls and similarly hued shirt work to frame his innocent boyish face. One visible hand rests softly on the right knee. Coming out from the bottom of worn blue jeans are Redd’s sheepishly positioned feet. While the left foot awkwardly pigeon-toes inward, the left is pushed in and back by Curtis’s aggressive leg. The result is a clumsy position that further relates Redd’s timidity. Conversely, Curtis is both bold and strong. In addition to being physically larger, the body is the center and focus point of the painting. Wig-like red hair is further exaggerated by thick red lipstick and heavy blue eye shadow. While Redd’s face seems youthful and soft, Curtis’s chunky features and large contrasts seem almost mask-like. Particularly interesting are Curtis’s hands. The right, long and graceful, differs greatly from the bony and masculine left one. Nevertheless, both show seemingly multiple layers of red nail polish, which serves to echo the burnt red tresses. Furthermore, Curtis’s exposed legs tell a story of their own. The right one is placed firmly in the nearest foreground while the left pushes backwards to touch Redd. What’s more, a small hole on in the right foot’s stocking reveals the same red nail polish covering Curtis’s right big toe.

Jackie Curtis and Ritta Redd visually appear to be a heterosexual couple yet the lines between female and male are blurred. Jackie, an androgynous name, appears masculine and brave, although dressed in drag. Redd, who ‘wears the pants’ in this painting, is depicted as smaller and softer. The unfinished grey background that surrounds this couple places them in a metaphoric ‘gray zone’ in which gender categories are unclear. Clothing and traditional gestures are no longer hints that help us determine the subjects’ biological sex. To Pamela Allara, in Jackie Curtis and Rita Redd, “gender is performed.” Hence the two are acting out identities rather than expressing the way they were naturally born. Allara understands this portrait by looking at the feet, reading the togetherness as a duality of their genders where the subjects are both male and female. In Phoebe Hoban’s recent book The Art of Not Sitting Pretty, she labels these body parts as “prurient feet,” thereby marking them with an unwholesome, immoderate and even sexual undertone. Thus Neel succeeded in capturing the sexual nuances of this couple, and for lack of a better saying, ‘down to their toes.’ By balancing the gender identities and blurring the traditional hints, Jackie Curtis and Ritta Redd blurs historically established lines between human biological sexes.

Jackie Curtis (1947-1985) was a “Warhol superstar,” a playwright, poet, cabaret singer and theater director. Born John Holder Curtis Jr., he invented the “glam rock” look of wearing glitter around his eyes and retro thrift-shop female fashions. His companion, Ritta Redd, was not a celebrity although he appeared in several films with Curtis. In an exhibition catalog essay for the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Richard Flood offers an amusing description of this painting using classic literary characters and real life analogies. “Huddled together like Hansel and Gretel in the presence of the witch,” Flood writes, “these two boys with transgendered dreams sit as if awaiting a court verdict.” Using other well-known tropes, Flood unpacks the subjects’ identities, “Jackie’s shoulder pads hint at an idealized Hollywood pantheon of femme fatales… Redd is a little more complicated. Part Tom Sawyer and part Little Lord Fauntleroy, he is the personification of knowing innocence. Even his awkwardly introverted feet seem oddly available to the advance of Jackie’s insinuatingly positioned right foot, with its open-toed high heel and torn black stocking revealing a curiously aggressive big toe.” In addition to being witty, these comparisons allow us to understand Curtis and Redd in a greater context as characters as well as individuals, as was characteristic of Neel’s work. Flood sums this up by writing, “It is one of those wonderful pictures by Neel that somehow gets much bigger than the subject ostensibly being portrayed.” Thus this portrait of two men dressed in unusual outfits and positioned in dubious poses in fact highlights the loftier questions of gender, sexuality and social roles.

... As de Beauvoir argued, “the body is not a thing, it is a situation.” In viewing Jackie Curtis and Rita Redd, one can see how Neel was of the same opinion. This painting plays with the way people negotiate gender and androgyny but does not go further to suggest a winner, but it does only that. What it does not do is prescribe how each sex ought to act, dress or negotiate power. In this respect, Neel allowed her subjects to be who they are. In the same way that Neel brought pregnant women into the public eye through works such as Margaret Evans Pregnant, Neel captured the experiences of marginalized people such as transvestites and carried them into the realm of high art. Remarkably, on November 11, 2009, this painting was sold at Sotheby’s Contemporary Art Evening Sale for $165,500,000, three times its highest estimate. This staggering price is evidence of today’s appreciation for Neel’s innovative and daring choices for what constituted art and worthy of being painted.

(http://www.americansc.org.uk/Online/Online_2012/neel.html)

Uploaded on Jul 16, 2017 by Suzan Hamer

Alice Neel

artistArthur

coming soon