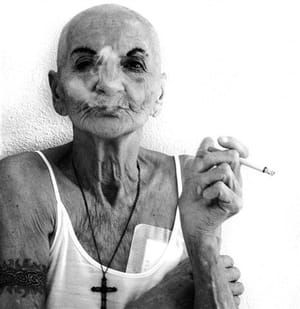

Germaine Greer

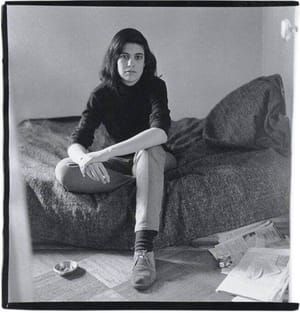

Diane Arbus

...(Diane would later tell Allan that another feminist subject, Germaine Greer, was “terrific looking, but I managed to make [her] otherwise.”)...

[https://www.thecut.com/2016/07/diane-arbus-c-v-r.html]

...For the years that she worked with her husband, Alan Arbus, as the stylist for his glamour photographs she had had no option but to make beautiful people look more beautiful. It was said that she was the best stylist in the business. Once the marriage broke down and Arbus struck out on her own, there was to be no more making people look their best. Maybe David thought he would learn something by watching Arbus at work. If he did, he must have been disappointed because, as soon as they were both in my room in the Chelsea hotel, she ordered him to leave. She couldn't work with other people in the room.

She seemed too birdlike and delicate to be lugging her outsize camera bag on such a warm day. Her thin cheeks were red with exertion and her fine fairish hair stood out around her face in wisps. I asked her whether she would like a rest or refreshment or something of the sort, and she refused in a tiny voice, without looking up from her camera bag. I'd have liked something myself, but this seemed not to occur to her. Throughout the session she spoke very little and always in a deceptively apologetic murmur. She avoided facing me, as she ferreted in the big bag and patted her many pockets. She set up no lights, just pulled out her Rolleiflex, which was half as big as she was, checked the aperture and the exposure, and tested the flash. Then she asked me to lie on the bed, flat on my back on the shabby counterpane.

I did as I was told. Clutching the camera she climbed on to the bed and straddled me, moving up until she was kneeling with a knee on both sides of my chest. She held the Rolleiflex at waist height with the lens right in my face. She bent her head to look through the viewfinder on top of the camera, and waited. In her viewfinder I must have looked like a guppy or like one of the unfortunate babies into whose faces Arbus used to poke her lens so that their snotty tear-stained features filled her picture frame (eg, A Child Crying, NJ, 1967). I knew that at that distance anybody's face would have more pores than features. I was wearing no make-up and hadn't even had time to wash my face or comb my hair.

Pinned on the bed by her small body with the big camera in my face, I felt my claustrophobia kick in; my heart-rate accelerated and I began to wheeze. I understood that as soon as I exhibited any signs of distress, she would have her picture. She would have got behind the public persona of Life cover-girl Germaine Greer, the "sexy feminist that men like". I concentrated on breathing deeply and slowly, and keeping my face blank. If it was humanly possible I would stop my very pupils from dilating. Immobilized between her knees I denied her, for hour after hour. Arbus waited me out. Nothing would happen for minutes on end, until I sighed, or frowned, and then the flash would pop. After an eternity she climbed off me, put the camera back in her bag and buggered off. A few weeks later she took an overdose of barbiturates and slit her wrists.

According to John Szarkowski, then director of the Department of Photography at New York's Museum of Modern Art, "Her real subject is no less than the unique interior lives of those she photographed." As if you could penetrate the interior life of a stranger by kneeling astride her and shoving a lens up her nose. It's Szarkowski's kind of mindless nonsense about what Arbus was really up to that obscures her genuine achievement. Interior life is probably not any photographer's subject; it was certainly not hers. In Arbus's hands everyone is en travesti; even women appear as female impersonators. She may have thought she was getting the mask off, but what she was photographing was actually the clumsy ill-drawn mask itself.

Arbus has been credited with stunning originality in her daring choice of subject, as if the tradition of portraying freaks were not as old as photography. Her Three Russian Midget Friends In A Living Room On 100th St of 1963 treats the subject exactly the same way as hundreds of commercial photographers before her, perching the little people on full-size furniture so their feet hardly touch the floor. Her vision developed little between 1963 and 1970 when she treated A Jewish Giant At Home With His Parents In The Bronx in a very similar way, though this time she emphasized the giant's outline with the black shadow thrown by the flash. What her work does not show is compassion, which is something to be grateful for. If I'd thought Arbus felt compassion for me I'd have socked her.

[Entire article at https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2005/oct/08/photography]

© Diane Arbus

Diane Arbus

artistArthur

coming soon