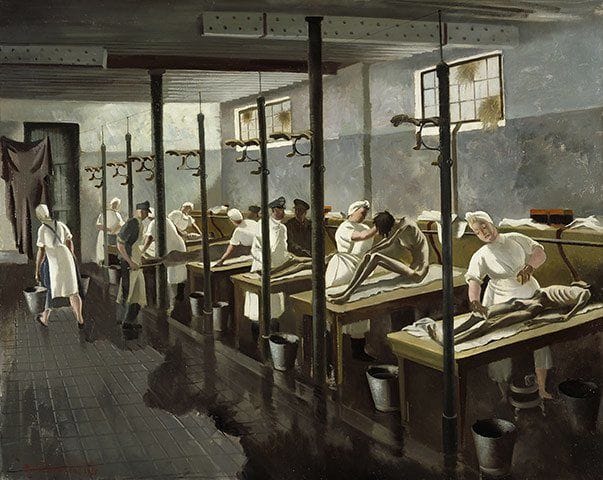

Human Laundry, 1945

Doris Clare Zinkeisen

In 1944, Doris Zinkeisen was commissioned by the Red Cross and St John Joint War Organization to record their work in north-west Europe – one of the very few women artists sent overseas. She visited Bergen-Belsen concentration camp soon after its liberation. Here, in Human Laundry (1945), she painted the stark, overt contrast between the rounded bodies of the carers and the emaciated former prisoners. But it is the orderly, almost industrial quality of this washing process that underlines the patients’ dehumanised condition.

(https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2011/apr/08/women-war-artists-imperial-museum-in-pictures)

One of a group of works produced by Zinkeisen during her time as a Red Cross artist. The 'human laundry' consisted of about 2- beds in a stable where German nurses and captured soldiers cut the hair of the inmates, bathed them and applied anti-louse powder before they were transferred to an improvised hospital run by the Red Cross. The tension in the composition lies in the enforced dealings between the emaciated and feeble former inmates and the healthy medical staff treating them.

In 1944 Zinkeisen was commissioned by the Red Cross and St John War Organisation to record their work in north-west Europe, and was one of the few women war artists to be sent overseas. On 15 April 1945 British soldiers entered Bergen-Belsen concentration camp to find a scene of absolute horror. Ten thousand corpses lay unburied, and around 60,000 starving and sick people were packed into the camp’s barracks without food or water. Doris Zinkeisen arrived soon afterwards. Human Laundry is arguably the most powerful work produced by any of the artists who were present. Zinkeisen finds an effective motif in the contrast between the well fed, rounded bodies of the German medical staff and the emaciated bodies of their patients. Although the artist’s later account refers to ‘the German prisoners’, they were actually nurses and doctors from a nearby German military hospital pressed into service. The camp inmates needed to be washed and de-loused to prevent the spread of typhus before they could be admitted to the makeshift Red Cross hospital nearby.

‘The stable was used to wash any living creatures down before sending them into hospital to be treated. Each stall had a table on which to lay the patient – the German prisoners did the washing. The church was used as a hospital for those that were alive.’ Doris Zinkeisen The 'human laundry' was set up to combat the spread of Typhus and consisted of over twenty beds in a former stable. It was staffed by captured doctors from the German armed forces and German nurses. The inmates would be shaved, bathed and dusted with anti-louse powder before they were transferred to an improvised hospital run by the Red Cross.

(http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/38950)

Uploaded on Apr 1, 2017 by Suzan Hamer

Doris Clare Zinkeisen

artistArthur

Wait what?