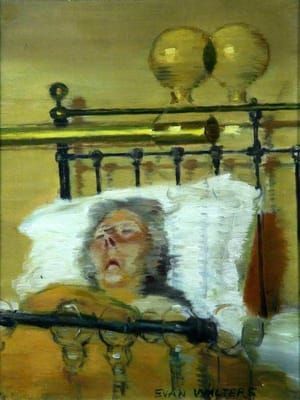

Still Life with Cricket Ball, 1940

Evan Walters

During the 20th century several important British artists began to paint features of visual experience rarely ever painted before, including subjective curvature, double vision and the body seen from the first person viewpoint. In doing so they broke with hundreds of years of pictorial convention, yet their experiments remain largely unrecognized.

...As a rather conventional social realist and society portraitist Walters might be all but forgotten were it not for a revelation he had one evening in 1936 when relaxing by the fire. He noticed when looking into the flames that his boot, interposed between him and the fire, had the characteristic doubled appearance associated with physiological diplopia, or ‘double vision’. The experience alerted Walters not just to double vision, but also to the indistinct properties of the peripheral field....

The revelation changed Walters’s life and his fortunes, but not necessarily for the better. He immediately began an intensive study of these visual phenomena....

Walters’s writings and an article and unpublished manuscript by Meinel reveal a well-informed understanding of visual perception that underpins a detailed theory of artistic depiction. Both Walters and Meinel were clear about the historical significance of Walters’s discovery. In his words: ‘in vision itself little advancement has been made since the adoption of perspective by artists some centuries ago. Consequently all pictures in existence, without exception, are painted as though their creators had only one eye in their heads, similar to a Cyclops’.

Even if he overstated his case, he was broadly right. With the possible exceptions of Cézanne (whose example Walters came to admire), Bonnard and Giacometti, very few artists had even tried, let alone found a successful way to represent the binocular aspects of visual experience in a two-dimensional image. Not only had Walters done this with some success, he had also tackled the complex and elusive contents of the peripheral visual field, and his obsession with conveying the actuality of visual experience even led him to include his own semi-transparent nose in various compositions of the 1940s, such as Still Life with Cricket Ball 1940. Other than the illustration of the view of his own body used by Ernst Mach in Analysis of Sensations of 1897, this seems to have been an unprecedented artistic act, and almost completely revoked the pictorial conventions imposed 5 centuries earlier by Alberti’s window metaphor.

(http://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/23/as-seen-modern-british-painting-and-visual-experience)

Uploaded on Nov 11, 2016 by Suzan Hamer

Evan Walters

artistArthur

coming soon