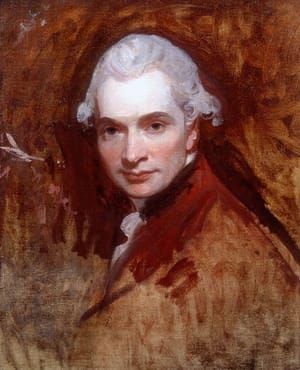

Self Portrait, 1784

George Romney

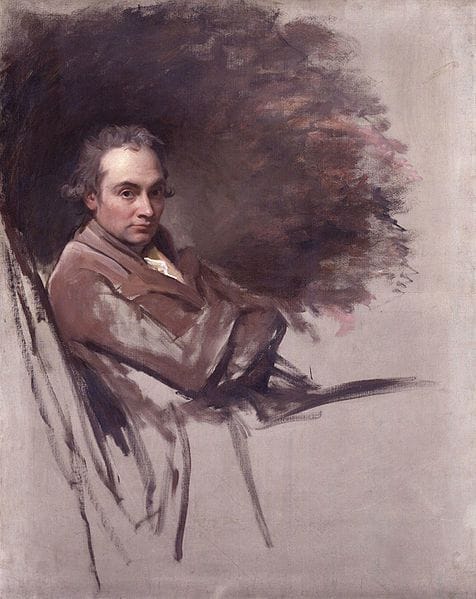

This portrait was painted in 1784 when Romney was fifty and staying at Eartham, the home of his friend, the poet, William Hayley. He gave the painting to Hayley who said it successfully conveyed Romney's 'pensive vivacity and profusion of ideas.' In this unfinished self portrait Romney's crossed arms and unflinching gaze reveal a watchful figure wrapped up in his own thoughts.

[http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw05424/George-Romney]

Romney was retiring, evasive, and never publicly communicated the range of his ambitions. He wanted to be more than a portrait painter. He dabbled in history, landscape, myth - the kind of grand art for which there was no market in hardnosed Britain. The emotion comes out in his portraits, which give their subjects subtle shades of reserve, tints of introspection; in his series of portraits of Emma, later Lady Hamilton, he pours out his sexual fantasy in a variety of costumes and settings.

Distinguishing features: Melancholy cripples the man in this painting, and spiritual impotence has laid him low. Romney is not even all there, his body trailing off in a few limp lines and flaccid, unfinished patches of enervated pink-brown. The cloud that surrounds his pale, nervous face and grey hair is not exactly a storm, more a smoky aftermath of energies long since dissipated. This painting is aesthetically radical to the point of self-mockery; it is quietly violent. Romney was said to have rushed it, but the mood of unfinished, hesitant, attention-deficit frustration is intentional. The half-empty canvas is a shocking thing to see - more so, perhaps, than in a modern painting, in which empty space has become a convention.

Advertisement

Romney portrays himself as a ruin. The cult of the broken, the unfinished and the ruinous was everywhere in the late 18th century. Far from leading to a cocky confidence in human endeavour, the Enlightenment brought a suspicion of progress, and an obsession with ruins - captured by Romney's contemporary Henry Fuseli in his nude self-portrait The Artist Moved by the Grandeur of Antique Fragments (1778-9), in which he sits overcome by the massive severed hand and foot of the colossal statue of Constantine in Rome.

Romney does not give himself a heroic relationship to the past, but instead depicts himself as a relic. His social facade - the hair, the elegant grey and pink tones of the painting, the way that instead of presenting himself as an artist at work he addresses us as one urbane, polite person to another - is a shell that is collapsing before our eyes. He sits, arms folded, jacket around him, slumped back like an invalid; his hair, while fashionable, is also madly twisting and slightly pathetic; most of all, his inability or lack of will to finish the painting is a confession of decline and fall.

Because his picture remains a patchy, indecisive trace on a partially bare canvas, we see Romney himself, the subject of the painting, as a half-man, not quite achieved, not quite able to exert influence on the world, to exist. It is a extraordinarily negative self-portrait, as Romney looks hard and cold into the mirror and finds himself wanting. He disappears as he tries to make himself appear.

[https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2002/jun/15/art]

Uploaded on Nov 27, 2017 by Suzan Hamer

George Romney

artistArthur

coming soon