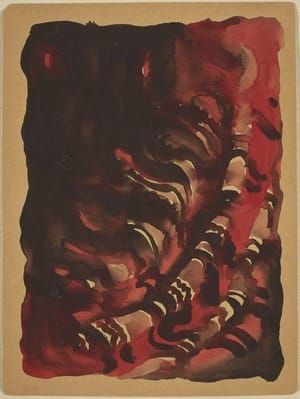

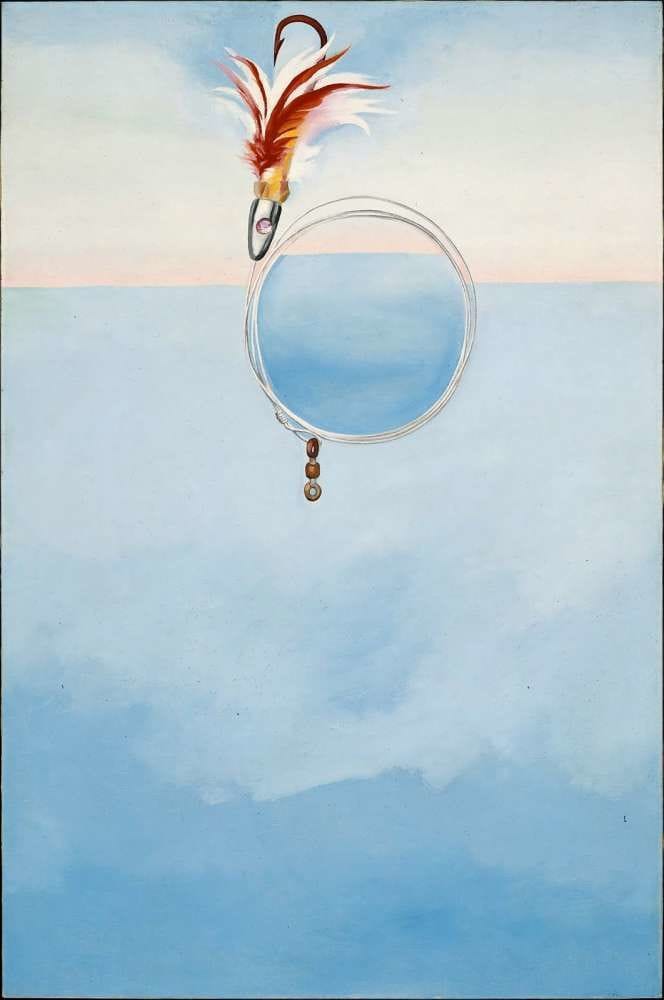

Fishhook From Hawaii No. 2, 1939

Georgia O'Keeffe

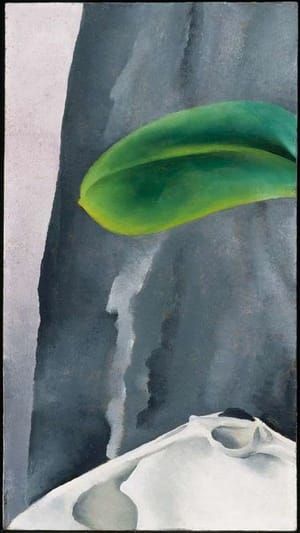

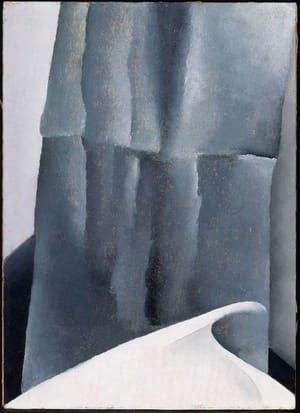

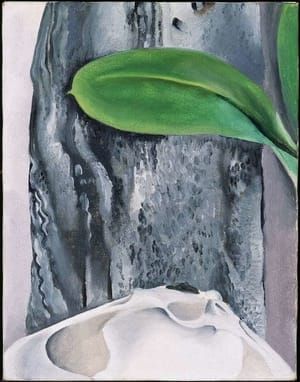

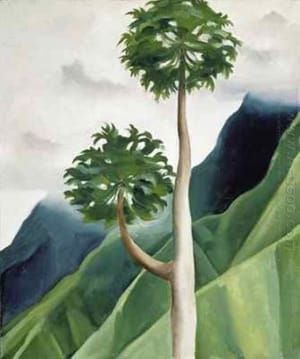

Georgia O’Keeffe visited Hawaii in early 1939 at the invitation of the Dole Pineapple Company. N. W. Ayer, Dole’s advertising agency, had offered to pay for her travel and living expenses for the duration of her stay if, upon its conclusion, O’Keeffe submitted to them two paintings of any subject suitable for use in the corporation’s advertising materials. O’Keeffe agreed, and spent January through April of that year in Honolulu and Maui. The experience inspired her to create a number of botanical still-lifes, seascapes, landscapes, and two images of fishhooks, including “Fishhook From Hawaii No. 2.” Once she returned to New York, O’Keeffe sent to Charles Coiner, art director of N. W. Ayer, a painting of a papaya tree and one of a red heliconia flower. By depicting a papaya tree, O’Keeffe had unwittingly selected a fruit grown and sold by Dole’s competitors. Coiner immediately shipped O’Keeffe a large budding pineapple plant and she obligingly painted a replacement image. Despite her efforts to provide Dole with appropriate works, the corporation never chose to use O’Keeffe’s paintings in their ad campaigns for reasons that remain unclear.

O’Keeffe exhibited twenty Hawaiian pictures in the spring of 1940 at An American Place, the Madison Avenue art gallery that her husband, photographer Alfred Stieglitz, operated between 1929 and 1946. In the accompanying brochure, O’Keeffe wrote, “If my painting is what I have to give back to the world for what the world gives to me, I may say that these paintings are what I have to give at present for what three months in Hawaii gave to me … What I have been able to put into form seems infinitesimal compared with the variety of experience.” The exhibition was well received, with the influential art critic Henry McBride writing that O’Keeffe’s fishhook paintings had “a strange and mystical elegance.” (Henry McBride, “Georgia O’Keeffe’s Hawaii,” “The New York Sun,” February 10, 1940, p. 10).

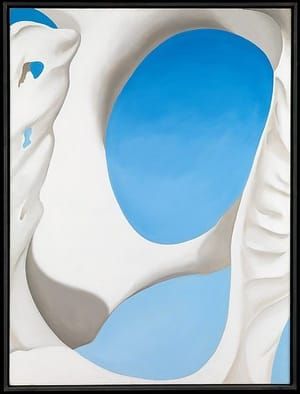

“Fishhook From Hawaii No. 2” shows a standard feather fishing lure attached to a coiled leader and swivel. These recognizable objects are set against a distant horizon line. The daringly modernist composition is remarkably empty of objects, especially in the lower register. Rather, the painting takes as its subject the many subtle variations on the color blue, accented by a touch of green at far left, which O’Keeffe found in the tropical Pacific Ocean off Hawaii.

O’Keeffe’s fishhook paintings represent an important conceptual breakthrough for the artist. Always intrigued by the concept of positive and negative space, she began in these works to explore a new and unique compositional structure based on the visual experience of looking through an opening. O’Keeffe perfected this organization in her pelvis series of the early 1940s, an extraordinary group of paintings that show the blue New Mexico sky through gaps in a stark white pelvis bone. In both the fishhook and the pelvis pictures, the central opening distorts that which is seen through it, almost as if it were a lens. For example, in “Fishhook From Hawaii No. 2,” the circle of coiled wire both intensifies and magnifies the blue sea and pink horizon line in the distance. These paintings are in many ways O’Keeffe’s sustained meditation on the nature of vision; after all, the human eye is itself a distorting and revealing lens. It is therefore fitting that, in “Fishhook From Hawaii No. 2,” the fishing lure’s red rhinestone eye glints back at the viewer, demonstrating that in the act of seeing we are often seen.

Heather Hole

October 2009

[http://www.mfa.org/collections/object/fishhook-from-hawaii-no-2-34869]

© 1939 Georgia O'Keeffe

Georgia O'Keeffe

artistArthur

coming soon