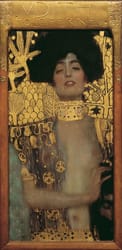

Judith and the Head of Holofernes, 1901

Gustav Klimt

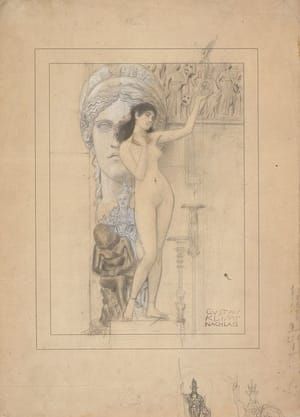

The painting reflects the refined decadence of turn-of-the-century Vienna, when the arts flourished as never before and the city produced a host of star names including – in addition to Klimt – Expressionist artist Egon Schiele, composers Gustav Mahler and Arnold Schönberg, and psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud.

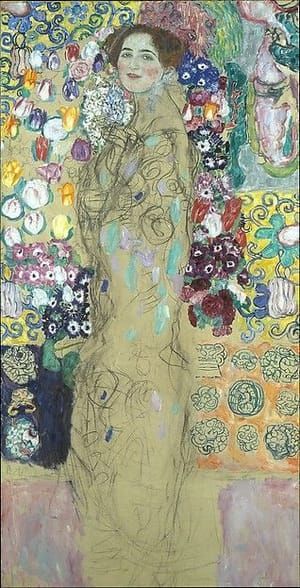

Klimt presents Judith as a predatory femme fatale. As the protagonist of the Bible story (who saved her city from the enemy forces of Nebuchadnezzar II by seducing and then decapitating his general Holofernes), Judith had traditionally been regarded as a chaste and heroic figure. Klimt, however, portrays her as a murderous man-eater, who slays Holofernes for reasons of revenge. He was one of the first people to show Judith in this light. Judith is not a heroic tableau, but a masterpiece of eroticism. Klimt has painted the figure and hands in a realistic manner and set them against a decorative, two-dimensional gold background.

(https://www.gemeentemuseum.nl/en/exhibitions/klimt_schiele)

Judith and the Head of Holofernes (also known as Judith I) is an oil painting by Gustav Klimt created in 1901. It depicts the biblical character of Judith holding the severed head of Holofernes.

When Klimt tackled the biblical theme of Judith, the historical course of art had already codified its main interpretation and preferential refiguration. In fact, many paintings exist, describing the episode in a heroic manner, especially expressing Judith's courage and her virtuous nature. Judith appears as God's instrument of salvation, but the violence of her action cannot be denied and is dramatically shown in Caravaggio's rendering, as well as those of Gentileschi and Bigot. Other representations have chosen the subsequent moment, when a dazed Judith holds Holofernes' severed head, as Moreau and Allori anticipate in their suggestive mythological paintings.

Klimt deliberately ignores any narrative reference whatsoever, and concentrates his pictorial rendering solely on Judith, so much so that he cuts off [ha ha] Holofernes' head at the right margin. And there is no trace of bloodied sword, as if the heroine would have used a different weapon: an omission that legitimates association with Salome. The moment preceding the killing — the seduction of Nebuchadnezzar's general — seems to coalesce with the conclusive part of the story....

Judith's face exudes a mixed charge of voluptuousness and perversion. Its traits are transfigured so as to obtain the greatest degree of intensity and seduction, which Klimt achieves by placing the woman on an unattainable plane. Notwithstanding the alteration of features, one can recognize Klimt's friend and maybe lover, Viennese socialite, Adele Bloch-Bauer, the subject of two other portraits done in 1907 and 1912, and also painted in the Pallas Athena. The slightly lifted head has a sense of pride, whereas her visage is languid and sensual, with parted lips in between defiance and seduction. Franz A. J. Szabo describes it best as a, “[symbol of] triumph of the erotic feminine principle over the aggressive masculine one.” Her half-closed gaze, which also ties into an expression of pleasure, directly confronts the viewer of all this. In 1903, author and critic Felix Salten describes Judith’s expression as one “with a sultry fire in her dark glances, cruelty in the lines of her mouth, and nostrils trembling with passion. Mysterious forces seem to be slumbering within this enticing female…” Although Judith had typically been interpreted as the pious widow simply fulfilling a higher duty, in Judith I she is a paradigm of the femme fatale Klimt repeatedly portrayed in his work. The contrast between the black hair and the golden luminosity of the background enhance elegance and exaltation. The fashionable hairdo is emphasized by the stylized motifs of the trees fanning on the sides. Her disheveled dark green, semi-sheer garment, giving the viewer a view of nearly bare torso, alludes to the fact that Judith beguiled the general Holofernes before decapitating him.

In the 1901 version, Judith maintains a magnetic fascination and sensuality, subsequently abandoned by Klimt in his Judith II, where she acquires sharper traits and a fierce expression. In its formal qualities, the first version illustrates a heroine with the archetypal features of the bewitching and charming ladies described by symbolist artists and writers such as Wilde, Vasnetsov, Moreau, and others. She revels in her power and sexuality—so much so, critics mislabeled Klimt's Judith as Salome, the title character from Oscar Wilde’s 1891 tragedy. To stress and reemphasize that the woman was actually Judith and not Salome he had his brother, Georg, make the metal frame for him with “Judith and Holofernes” engraved on it.

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Judith_and_the_Head_of_Holofernes)

33 x 17 in

Uploaded on Jun 20, 2013 by Mark Abramovich

Gustav Klimt

artistArthur

coming soon