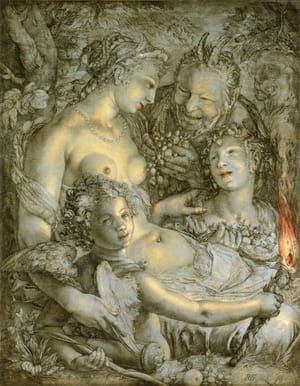

The Fall of Man, 1616

Hendrick Goltzius

In this magnificent image, Adam and Eve recline like mythological lovers in the Garden of Eden, portrayed at the very moment they become aware of their mutual desire. Having already taken a bite from the apple, Eve turns toward Adam with a knowing gaze as she tenderly touches his chest. Mesmerized, Adam gently draws Eve toward him with his left arm as he looks into her eyes with intense longing. Adam also holds fruit, a tender fig that he squeezes between the forefinger and thumb of his right hand, a gesture as laden with sensual overtones as is the partially eaten apple. The compelling emotional force of this moment is enhanced by the surrounding plants and animals, which Goltzius has painted in a bewitchingly believable fashion.

Goltzius entices his viewer to become fully engaged in this intimate encounter by placing the life-size figures of Adam and Eve close to the picture plane where one senses the fullness of their physical presence and the power of their mutual attraction. Adam and Eve’s bodies are perfectly proportioned, with skin that yields gently to the touch. As they lie there entirely naked except for the ground ivy that covers Adam’s genitals, light plays across their bodies, modeling Adam’s muscular body as well as Eve’s softer form with its paler, more transparent flesh tones. Nevertheless, their idealized bodies have a physicality that fully explains their inability to restrain their primal appetites. That failure will lead to their expulsion from Eden and humanity’s fall from grace.

So beguiling is this portrayal that one can almost understand how Adam and Eve remained oblivious to the dire consequences of their actions as they discovered these new and unexpected emotions. Yet, as is narrated in the book of Genesis (Genesis 3:1–7), Adam and Eve had been told not to eat the fruit from the tree in the midst of the garden lest they die. The serpent, however, persuaded Eve that eating this fruit would allow them to be like God, knowing good from evil. She partook of the fruit and then passed it on to Adam, who ate as well. Consequently, their eyes were opened, and, realizing they were naked, they sewed together fig leaves to cover themselves. God drove the couple from his earthly paradise, the Garden of Eden, and neither they nor their offspring would ever be allowed to return.

Goltzius’ seductive rendering of The Fall of Man differs in fundamental ways from the pictorial tradition of this biblical theme. Prior images, including Goltzius’ drawing of The Fall, c. 1597, and his large painting of 1608, now in the Hermitage, had depicted the couple standing or sitting at the moment when Eve was either receiving the apple from the serpent or passing it on to Adam. Here, as Adam languidly gazes at Eve, who is eating from the forbidden apple, his pose reflects that of his counterpart in Michelangelo’s ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, where Adam awaits the spark of life from God the Father. As exceptional as it was for Adam and Eve to be depicted as lovers reclining in their paradisiacal setting, it was even more unprecedented for a painting of them to focus on their rapt gazes and mutual yearnings rather than on the transfer of the apple.

Little in the demeanor of Adam and Eve indicates the grave consequences of their actions, although Goltzius alludes to the momentousness of the occasion. The animals surrounding the couple in the Garden of Eden provide a symbolic framework for how the viewer ought to respond to the scene. Most important to the biblical narrative, of course, is the serpent that leads Eve astray. Far from the evil and menacing creature that one often finds in such depictions, Goltzius’ serpent is sweet-faced and female-headed, a warning about the deceptiveness of appearances. The goat traditionally signified unrestrained lust and the unchaste; as such, it was frequently included in images of The Fall. Karel van Mander I (Netherlandish, 1548 - 1606), whose writings Goltzius would have thoroughly known, gave a particularly pointed symbolic interpretation for this animal. For him the goat also signified “the whore, who destructs young men, just [as it] browses and violates the young green shoots,” an interpretation that Goltzius has followed: the goat nearest Eve chomps on young grasses.

The elephant and hare in the far distance have different relationships to Adam and Eve. Both animals have turned their backs on the scene and are departing the area as quickly as possible. The hare probably leaps away in fear of the consequences of Adam and Eve’s actions, since fear is one of the attributes Van Mander gave to this animal. On the other hand, the elephant was traditionally associated with piety, temperance, and chastity, so little wonder that Goltzius depicted it in fast retreat.

The most fascinating and riveting of all the animals in the scene is the cat in the immediate foreground, which is so realistically painted that one can almost hear it breathe. Although the cat was traditionally viewed as a symbol of lust and sensual pleasure, for Van Mander this animal served as a warning to the viewer about being an unjust judge. The cat’s penetrating gaze, from which there is no escape, reminds spectators not to condemn others for the very vices of which they are themselves guilty.

The Fall of Man is among a number of paintings Goltzius executed between 1613 and 1616 that focus on lovers in a landscape, including Venus and Adonis, 1614, which depicts the goddess gently embracing Adonis as she, in vain, urges him to stay with her and avoid the hunt. Much as with Adam and Eve, the two figures gaze into each other’s eyes, with their young, idealized bodies arrayed in the immediate foreground for the visual enjoyment of the spectator. The style and character of Venus and Adonis, and all of Goltzius’ subsequent paintings, owe much to the influence of Sir Peter Paul Rubens, who visited Goltzius in Haarlem in June 1612 in search of an engraver to make reproductive prints after his paintings. Goltzius, who had turned his attention to painting around 1600 after his successful career as an engraver, had previously sought to master the rendering of flesh, which Van Mander considered to be one of the most difficult things to paint and thus a crucial test of a painter’s skill. It was only after Rubens’ visit, however, that Goltzius learned how to create sensual painted images by blending his brushstrokes to create the luminosity of flesh and by focusing on the emotions of love and longing. It is not known which of this Flemish master’s paintings Goltzius actually saw at that time, but one of them could have been a Venus and Adonis that was in the Delft collection of Boudewijn de Man (c. 1570/1575 – after 1644), who likely was the first owner of Goltzius’ The Fall of Man.

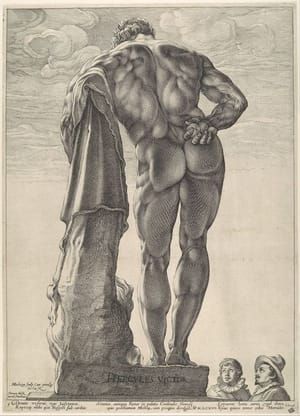

Although Rubens had a great impact on Goltzius’ painting style in the mid-1610s, no one would ever confuse the works of the two artists. Goltzius never assimilated the lessons of his experiences in Italy in 1590–1591 to the same extent that Rubens had during his prolonged stay there in the first decade of the 17th century. The idealization of classically inspired figures in Rubens’ paintings was of a different order than the idealization of comparable figures in Goltzius’ paintings. For example, even though Adam’s pose relates in many ways to that of the antique sculpture of the river god Tiber that Goltzius drew in Rome in 1591, Goltzius has given Adam’s body a sinuous, rhythmic flow reminiscent of the artist’s late 16th-century mannerist style.

Goltzius must have based this composition on a number of drawings that he made from life. The goat nearest Eve, for example, is practically a mirror image of a metalpoint drawing he made in 1591–1594. Documents indicate that Goltzius also made a drawing of a cat, which was probably similar in character to the goat drawing. Drawings likely served as models for both Adam and Eve since the poses of both figures are found in other paintings. For example, Goltzius used Eve’s pose for one of the daughters in Lot and His Daughters, 1616, in the Rijksmuseum. Interestingly, by 1616 Goltzius had already used Adam’s pose twice when depicting a female figure. In his Vertumnus and Pomona of 1613, the goddess of fruit reclines in a landscape just as Adam does, but facing the opposite direction. In 1615 she appears in mirror image, in the pose that Goltzius would use for Adam one year later. It is testimony to the artist’s genius that each of the permutations of this figure seems so compellingly natural and integrated into its narrative.

Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., April 24, 2014

(https://www.nga.gov/Collection/art-object-page.95659.html)

Notice, the snake in the tree has a female face (as did that of Michelangelo's Sistine Ceiling snake).

(http://art-now-and-then.blogspot.nl/2014/05/hendrik-goltzius.html)

Uploaded on Oct 8, 2017 by Suzan Hamer

Hendrick Goltzius

artistArthur

coming soon