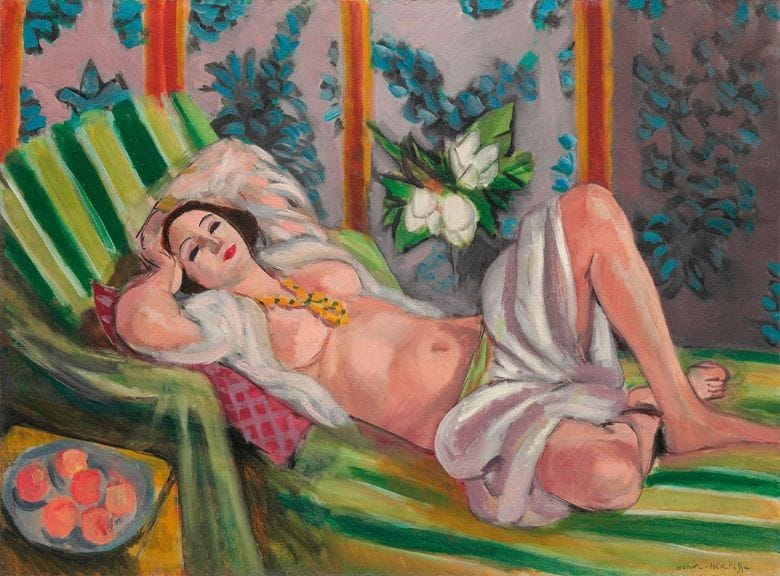

Odalisque couchée aux magnolias, 1923

Henri Matisse

‘In 1923 Matisse was at the height of his powers,’ Pylkkänen continues, ‘and here he entrances us with a sumptuous painting of his favourite model, Henriette Darricarrère, basking in bright sunlight, reclining in the luxurious surroundings of his Nice studio. When you see it, you’re seduced by the radiant colours and the perfect balance and proportion of the composition. It is an iconic painting which describes Matisse at his very best.

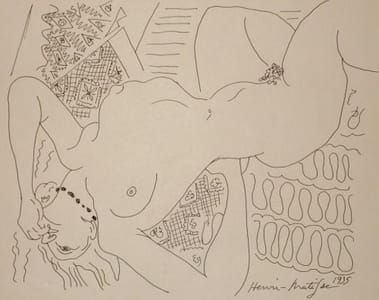

Henriette Darricarrère was among the most striking and elegant models in art history. ‘She adopted these extraordinarily sculptural poses, which define her as one of the most recognisable models of the 20th century: many of Matisse’s greatest sculptures are based on Henriette, and I would argue that his greatest paintings of her retain this sculptural quality,’ Pylkkänen says.

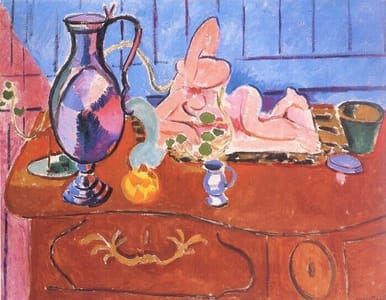

Darricarrère represented for Matisse the ideal subject for the type of painting he wanted to execute when he moved to the south of France from Paris in 1921. ‘He wanted to create great sensual paintings, full of colour, full of light,’ Pylkkänen explains. ‘But he also wanted to create canvases that had a good pictorial structure, so he would spend a huge amount of time looking for props to use in his studio, whether it be the screen he’s set behind the odalisque, the chaise longue, the striking magnolias or the bowl of vibrantly coloured oranges.’

By the early 1920s, too, Fauvism had played its course. Colour had been liberated. ‘After the First World War there’s a sense of return to order. Matisse, for his part, like Picasso, created a new visual vocabulary involving colour, structure and form — but most of all balance and serenity. This picture has all of that,’ Pylkkänen notes.

‘It is a picture that we all recognise immediately from our art-history books, and which captivated me from the moment that I first saw it at the Rockefellers’ Hudson Pines home just outside New York. It hung in the sunny living room, where Henriette looked very much at home. She seemed as relaxed as perhaps the many visitors had felt in that beautiful space. It was a moment I will never forget.’

At the time that he painted Odalisque couchée aux magnolias, Matisse was possibly at his happiest, Pylkkänen suggests: ‘He was working very freely, with an incredible expressiveness. The canvas of the Odalisque is painted from one corner to the other, and there’s a great sense of plasticity.’ The paint is unvarnished, too; Matisse intentionally kept the pigment chalky in order to mimic the raw, synthetic surface of the cloth and textiles that he was depicting.

[http://www.christies.com/features/5-minutes-with-Henri-Matisse-Odalisque-couchee-aux-magnolias-8903-3.aspx?sc_lang=en&cid=EM_EMLcontent04144A23A_0&cid=DM163989&bid=123476965]

Uploaded on Feb 24, 2018 by Suzan Hamer

Henri Matisse

artistArthur

coming soon