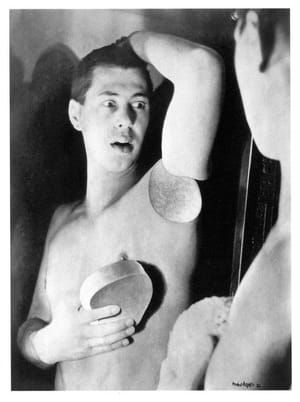

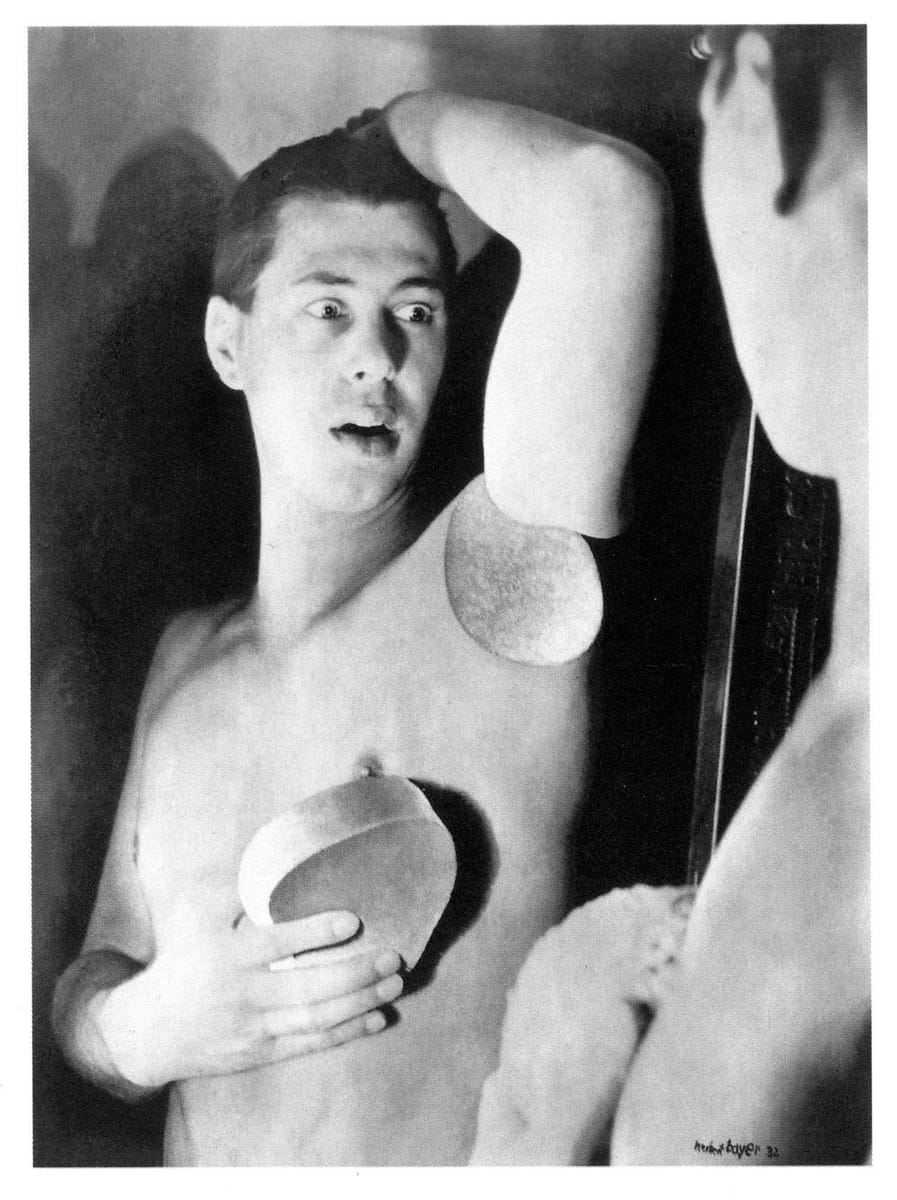

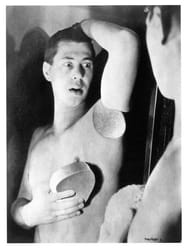

Humanly Impossible (Self-Portrait) (Menschen unmöglich (Selbst-Porträt)), 1932

Herbert Bayer

Negative Date 1932;

Print Date 1932–37

Herbert Bayer joined the Bauhaus in 1921 as a student, and his productive relationship there with László Moholy-Nagy led to his avant-garde photographic and typographic experiments. When the Bauhaus moved from Weimar to Dessau, in 1925, Bayer led the newly established workshop in printing and advertising. In 1928, following director Walter Gropius’s resignation, Bayer left, too, and relocated to Berlin, where he became the art director of the German edition of Vogue magazine and of Dorland Studio, an international advertising agency.

At the Bauhaus, Bayer worked with photographs in designing many of the school’s printed materials and advertising graphics, but his own exploration of photography was very limited. During his time at the school, he married the photographer and Bauhaus student Irene Angela Hecht, and when he left he began taking his own pictures in earnest, quickly moving from unmanipulated photographs to dramatic montages.

A series of 11 photomontages, titled Man and Dream (Mensch und Traum), includes Humanly Impossible (Self-Portrait) (Menschen Unmöglich [Selbst-Portrat]). In this picture Bayer observes his reflected double in a mirror. A slice of his arm is severed from his torso, as if he were an armless classical sculpture. Although the picture is playful, reflecting both Dada humor and Surrealist dream states, the horror on Bayer’s face could reflect something darker, perhaps the physical and psychological traumas of World War I and the growing fears that such a cataclysmic nightmare might recur; Man and Dream was completed in 1932, the year before the Nazis shut down the Bauhaus.

To make this work Bayer started by taking his picture in a mirror. Knowing that every added mark might betray the illusion he wanted to project, he worked to scale. He exposed the self-portrait negative to a 30 by 40 centimeter (11 13/16 by 15 ¾ inch) sheet of photographic paper pinned to an easel in a darkened room, and he then mounted the resulting print on board and worked up the image. To shape the fragmented arm and its missing slice, he painted over the photograph with gouache containing an opaque white Pigment (such as chalk) that acted as an effective concealer and provided good reflectivity. With an airbrush, the turn-of-the-century tool favored by graphic designers, Bayer then deposited an atomized spray of gouache and watercolor to smooth irregularities and create seamless transitions from paint to photograph. In the next stage, this maquette was photographed and printed to scale, signed in the lower-right corner, and photographed again; every subsequent print was made from this third negative. Bayer could have made the montage in two steps, but the extra generation softened his transitions, thus deepening the illusion. The rough surface texture of the warm-Toned paper that he chose (a paper marketed to professional photographers) helped further unify the disparate elements.

Bayer’s self-portrait as both classical sculpture and amputee dispenses with the idea of the unitary self and takes a stand against the idealized Aryan body found in Nazi art and mass culture in the 1930s. The uneasy political climate of the period affected the way in which other artists—including Johannes Theodor Baargeld, Hans Bellmer, and Hannah Höch—approached the human body, many of them turning to photomontage for its subversive political effect. To oppose the corporeal perfection and psychic hygiene of the Fascist propaganda machine, these artists created hybrid anatomies of forms that were animate, but only ambivalently so. —Lee Ann Daffner, Roxana Marcoci

(https://www.moma.org/interactives/objectphoto/objects/83703.html)

15 x 11 in

Uploaded on Feb 14, 2017 by Suzan Hamer

Herbert Bayer

artistArthur

coming soon