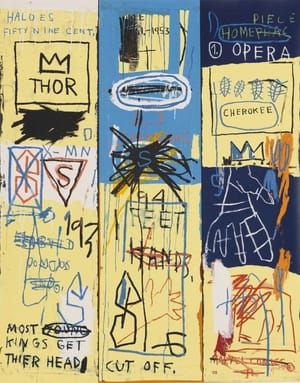

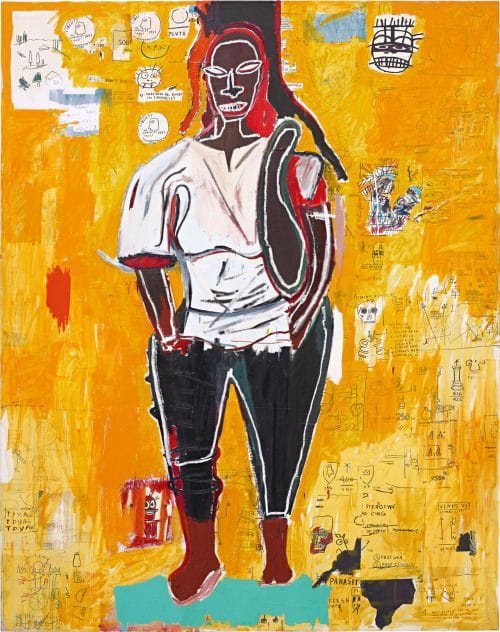

Big Joy, 1984

Jean-Michel Basquiat

Sold for £2,617,250 at the Contemporary Art Evening Sale, 10 October 2012.

“I just felt really right. I felt like I was glad that I stuck it out and I was glad that I’d had these hard times.” - Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1985

Big Joy, executed in 1984, shows Jean-Michel Basquiat at the height of his powers and the pinnacle of his artistic career. Basquiat’s short-lived career was notoriously troubled and tormented. The artist had ascended spectacularly through the ranks of New York’s high-society art world in the early 1980s, only to succumb to exploitative social and professional pressures, leading to his untimely death at the age of 27. Big Joy expounds upon the most important themes in the artist’s oeuvre, issues which underline his artistic raison d’être: race and identity. Basquiat was the first black artist to break into the white dominated art world and his work reflects the struggles and hardships of a deprived African-American in the face of this ostensible dominance. As a result, Basquiat continually questioned his identity and place in the world, living a life of contradictions and contrasts.

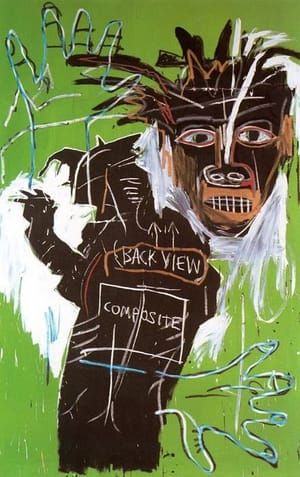

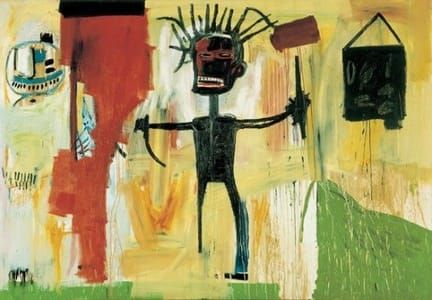

Big Joy, as with much of Basquiat’s work, concentrates on the human figure. The focal point is the immense and overwhelming central figure of a black lady – Joy. Standing at roughly seven feet tall, the female figure dwarfs the viewer. The dark tones of the face, hair, arms and legs jump out against the vibrant aurulent backdrop. The figure is thick set, strong and relaxed; she dominates the composition and exudes confidence. Big Joy is a panorama of the artist’s stream of consciousness, depicting an associative attempt on African-American culture. Not only is Basquiat constructing a social commentary on racial inequality and integration, but he also becomes more personal – he’s painting a complex and existential portrait.

“Basquiat’s work documents the progressive construction of the artist’s discordant identity, of a man grappling with the reality that he could make little use of the patterns available to him – either of his father’s existence as an accountant who adopted the ideals of the white middle class, or the ghetto kid attitude of the graffiti sprayer. Basquiat’s numerous self portraits may well be ideal blueprints of the artist as an enraged hero; but they are also terrifyingly bleak documents of inner turmoil and great loneliness.” (L. Emmerling, Basquiat, Cologne, 2006, p. 88)

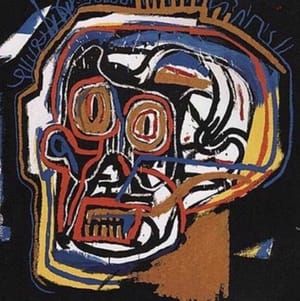

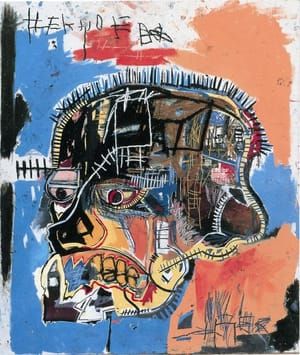

This figure derives aesthetically and subjectively from Basquiat’s earlier paintings. The face itself is characteristically crude with a primitive mask-like rendering with jewel eyes that bore into the viewer. This is reminiscent of the African mask influence in Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon of 1907 where he departs from traditional European painting. Further, the gritted grid-like mouth offers a disturbing glimpse into the anxious mind of the young artist. It’s the female subject, with her life-like body shape, proportionate limbs and human demeanor that makes Big Joy so singular. Basquiat’s early portraits pay homage to his black American heroes, predominantly male athletes and musicians such as Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Joe Louis, and Cassius Clay. His portraits of the early 1980s marry the gritty urbanism of his street graffiti with his raw and primitive symbolism. This work can be conceived as a triumph, a celebration of Basquiat’s new found success, wealth, critical acclaim and acceptance into high society. Several coins visible in the upper left corner rain down onto the figure. The subject is engulfed by a sea of spectacular gold and stands on a patch of fresh green grass, all alluding to Basquiat’s new found fame and wealth. Even the very title of the work, Big Joy, is indicative of this personal self-fulfillment. In February 1985, shortly after the execution of Big Joy, Basquiat featured on the cover of the New York Times Magazine with the headline ‘New Art, New Money – The Marketing of An American Artist’. Given that five years previously, Basquiat had been living on the streets tagging subways, many would see this as the ultimate rise to success.

Big Joy was given pride of place in the seminal exhibition Jean-Michel Basquiat at Mary Boone Michael Werner Gallery, New York, in 1985. The work was purchased from the exhibition and has remained in the same private collection since (although it has been on long-term loan from the mid-1990s to the Musée d’art moderne et contemporain in Geneva and then from the early 2000s to the Museum der Moderne, Salzburg, being frequently on public display). The figure reportedly had dark shoes when the painting was purchased (Basquiat painted over the shoes with a turquoise block of paint during the exhibition). Basquiat’s first solo gallery show was with Galleria Emilio Mazzoli, Moderna in 1981. Shortly after, he started to work directly with the New York Gallerist Anina Nosei. Nosei provided Basquiat with a stable studio space in the basement of her gallery and an endless supply of materials enabling him to paint as he wished. Mary Boone in New York and Bruno Bischofberger in Zurich would become Basquiat’s principal gallerists and both played a key role in the artist’s career.

Many of Basquiat’s recurring motifs are present in Big Joy. A skeleton is evident in the middle right of the canvas, the words “PARASIT”, “FLESH” and “SKIN” are visible in the lower right corner. The recurrent portrayal of anatomical components in his work stems from a chance encounter and early fascination with human anatomy. When he was seven, Basquiat was hit by a car whilst playing in the street. During a traumatic hospitalization that resulted in the removal of his spleen, Basquiat’s mother gave him a copy of Gray’s Anatomy which had a profound effect on him. Basquiat recalls, “I remember it just being very dreamlike, and seeing the car sort of coming at me and then just seeing everything through sort of a red filter” (B. Johnson and T. Davis, interview with Jean- Michel Basquiat, Beverly Hills, California, 1985). Furthermore, in typical chaotic fashion, Basquiat has written “TPYA©” in the lower left corner, suggestive of his earlier days, as SAMO©, the rebellious graffiti poet of lower Manhattan in the late 1970s. Basquiat continually paid tribute to the culture of graffiti: “I remember when I first moved to New York, half the walls of downtown were covered with SAMO© graffiti. It was cryptic. It was political. It was poetic. It was funny” (B. Johnson and T. Davis, interview with Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1985).

[http://wishflowers.tumblr.com/tagged/art/page/12]

© 1984 Jean-Michel Basquiat

Jean-Michel Basquiat

artistArthur

coming soon