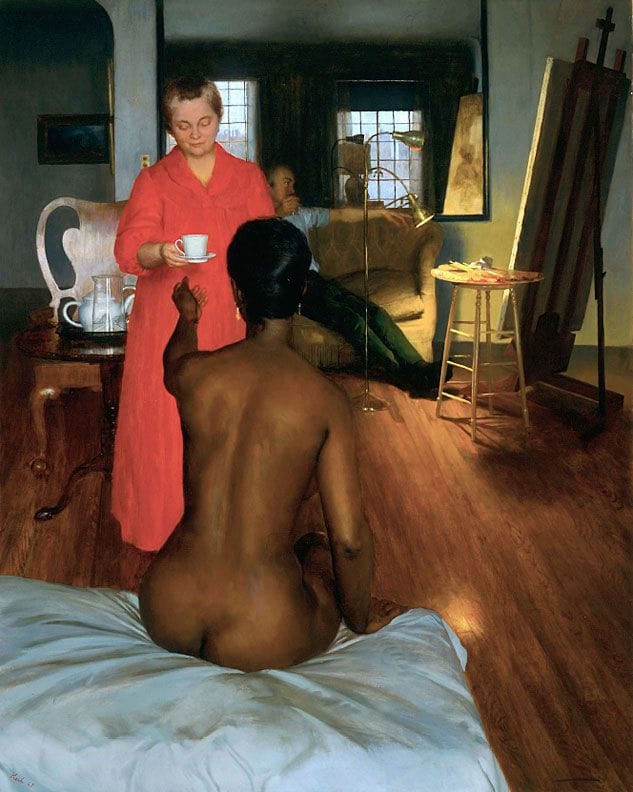

Interlude, 1963

John Koch

Another semi-self-portrait with wife Dora, berobed, adding to the domestic and refreshingly interracial scene. Koch was a story-teller as much as a painter.

http://www.advocate.com/arts-entertainment/art/artist-spotlight/2013/07/27/artist-spotlight-john-koch?page=0,0

Artists’ works reflect the values of their times as well as their own points of

view.

“I am intensely concerned with the believability of my painted world. Again and again I invent objects, people, and even places that do not exist.”

(Seeing America, 275)

Interlude reminds the viewer that the long history of representational art—portraiture, genre painting, and still life—continues to flourish in America.

The story of artist and model is an old and traditional art theme. Here artist John Koch presents a moment in his studio when both artist and model relax, the nude model to enjoy a cup of tea while the artist gazes at his partially completed work on the easel. The African American model dominates the

foreground as Koch sets her dark velvety back against the white bed sheet and the vibrant red robe of the third person in the painting, a white woman who offers a cup of tea. As Koch draws the viewer deeper into the room, the curved lines of the model’s body are repeated in the Queen Anne chair, glass pitcher, teapot and doorway arch. Contrast these curving lines with the diagonal lines on the painting’s right side. There the receding floorboards, the long legs of the lounging artist, and the angle of the easel create the believable space of the studio. The circles of light accenting the artist in the background help the muted tones on the right balance the powerful push-pull of

the colors on the left.

Koch’s compositional skills and ingenuity are evident in his placement of the large rectangular mirror behind the couch. What the viewer imagines at first as windows in the painting’s background are revealed to be the reflection of the room behind the model. Also striking is that the 3 figures neither engage with the viewer, nor do they engage in eye contact with each other. The model’s dramatically foreshortened arm reaches back to the older woman, but she does not touch the teacup; neither does the robed white woman look directly at the naked young black model.

Believable scene of art and model: yes. Every inch of the painting is “photographically” correct—the three-dimensionality of the room, the gleam of the highly polished floor, the accurate details of the gooseneck lamp and other decade-appropriate objects. The apartment/studio, and the two women (Koch’s wife, Dora, and the model, Rosetta Howard) appear in many John Koch paintings. Yet he admits to “staging” his scenes—and leaves the viewer to imagine his purpose.

Is Interlude simply a portrayal of a relaxing break in the process of painting? Or does it also gesture toward some of the social changes of 1963, the

year it was painted? Consider, for instance, the implications of the multiple reversals—the windows revealed to be reflections, and, at the center, a white

woman serving a woman of color. (http://mag.rochester.edu/seeingAmerica/pdfs/69.pdf)

Uploaded on Jun 5, 2016 by Suzan Hamer

John Koch

artistArthur

Wait what?