Portrait of Isabella d'Este

Leonardo Da Vinci

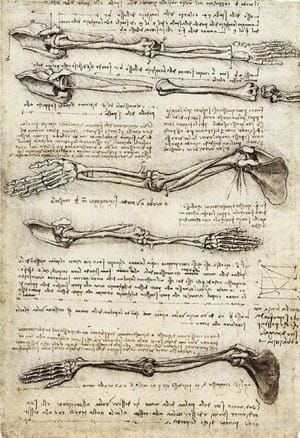

Leonardo da Vinci left Milan in 1499 when the French army invaded Italy. On his way to Venice he stopped at Mantua, where Isabella d’Este asked him to paint her portrait. This famous drawing is a sketch for the portrait that was never painted; despite its fragile state of conservation, it is one of Leonardo’s finest head-and-shoulders portraits, here with the head in profile. It is also the only known drawing by the master that is highlighted with several colored pigments.

Isabella d’Este wanted to have the best possible portrait of herself painted, sculpted, or struck on a coin. In 1498, she determined to surround herself with the most eminent contemporary artists and find the best portrait painter, one who could produce a perfect imitation of nature; her choice fell on Leonardo da Vinci. When in Venice, Leonardo da Vinci showed his portrait of Isabella to his friend Lorenzo da Pavia, who wrote to the Marchesa on March 13, 1500: "Leonardo da Vinci is in Venice, he has shown me a portrait of Your Ladyship that is very lifelike. It is very well done and could not possibly be better." Despite Isabella’s insistence, the painting was never done.

In his sketch, Leonardo used various pigments (sanguine and chalk), different tones of black, and finely hatched and smudged red and yellow ochre to obtain the passage from light to shadow on the face and hair. Contrary to claims by Vallardi and almost all subsequent authors, there are no traces of pastel. A very pale white applied to the bosom (covered by a piece of lace called a “modesty piece”), the forehead, and the cheek, accentuates the slant of the shoulders and the shadow of the neck.

Though unfinished, this sketch is remarkable for its proportions, and for the foreshortening of the bust; it is also striking for the ambiguous choice of pose. The perfectly linear profile, eyes gazing beyond our field of vision, contrasts with the turn of the body. The portrait in profile may have been the choice of the Marchesa herself, who was thus portrayed on the bronze medal made by Gian Cristoforo Romano in 1497-1498. The clear-cut profile of the face, its use of space, the slant of the turning shoulders, the attention paid to the folded hands and the finger pointing to the book are all touches that distinguish this work from the Portrait of Cecilia Gallerani (1489-1491, Cracow, Czartoryski Museum) and from the Portrait of an Unknown Woman (c. 1495-1500, Paris, Musée du Louvre). This portrait of Isabella d’Este can be seen as the fruition of Leonardo’s experimentation since the 1490s, and a preview of what was about to follow: the cartoon of the Virgin and St Anne (London, National Gallery), and the Mona Lisa (Paris, Musée du Louvre). The portraits of Isabella d’Este and the Mona Lisa seem to represent Leonardo’s "progressive idealization of the portrait"—in other words, his attempt to create portraits that were lifelike yet of a perfection related to universal beauty.

Black and red chalk with stump, ochre chalk, white highlights on the face, throat, and hand. Original black chalk lines are visible in several places: face, hair, veil on the forehead, neck, garment covering the breast, left shoulder. Paper prepared with white in the upper left and right parts.

H. 61 cm; W. 46.5 cm

[https://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/portrait-isabella-d-este]

© Leonardo Da Vinci

Leonardo Da Vinci

artistArthur

coming soon