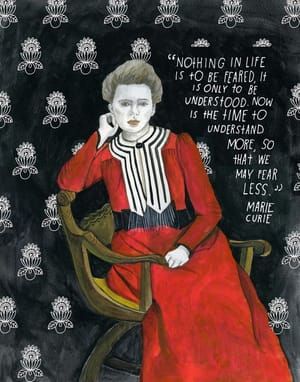

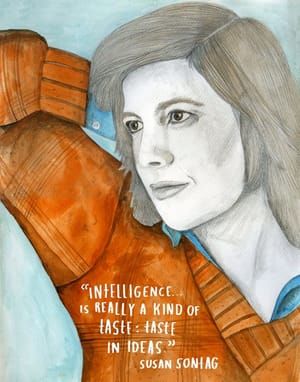

Sylvia Plath, 2013

Lisa Congdon

Sylvia Plath (October 27, 1932 – February 11, 1963) has been called an “addict of experience,” a tragic literary blonde, a victim of her generation and her medication. Beneath these partly true yet invariably reductionist labels, however, lies the immutable fact that she was, above all, one of the most celebrated and influential poets of the twentieth century, with a remarkable gift for moving the hearts of millions while struggling to still her own.

From an early age, Plath embodied a chronic osmosis of profound melancholia and boundless literary talent. Her dissonant relationship with life bursts open in her journal from age eighteen, where she writes:

With me, the present is forever, and forever is always shifting, flowing, melting. This second is life. And when it is gone it is dead. But you can’t start over with each new second. You have to judge by what is dead. It’s like quicksand… hopeless from the start. A story, a picture, can renew sensation a little, but not enough, not enough. Nothing is real except the present, and already, I feel the weight of centuries smothering me. Some girl a hundred years ago once lived as I do. And she is dead. I am the present, but I know I, too, will pass. The high moment, the burning flash, come and are gone, continuous quicksand. And I don’t want to die.

In another diary entry, she laments:

Life is a gentleman’s agreement to grin and paint your face gay so others will feel they are silly to be unhappy.

Yet even in the face of debilitating mental illness throughout her life, Plath maintained an astonishing daily routine, fueled in part by her anxious insomnia and in part by the very creative restlessness that lent her her poetic prowess.

In 1950, Plath enrolled in Smith College. It was there that she, an excellent student, formally submerged herself into the literary world. After editing The Smith Review, she was invited to serve as a guest editor at Mademoiselle magazine the summer before her senior year – a prestigious assignment that precipitated her notorious month in new York City. She graduated from Smith with honors and moved to Cambridge, England, to continue her studies at Newnham College on a Fulbright scholarship.

There, Plath met fellow poet Ted Hughes in February of 1956. It was one of literary history’s steamiest encounters, but only four months later, they wed and embarked upon a marriage that would be at once a famed partnership at the intersection of literature and love and a highly controversial dynamic that continued until death did them part in 1963, when Plath took her own life by sticking her head in oven and turning on the gas. She was only thirty.

In 1982, her Collected Poems earned Plath one of the few posthumous Pulitzer Prizes ever awarded. She was also a woman of multiple, if lesser-known, talents, from her surprisingly deft drawings and her children’s books – including one posthumously illustrated by the great Sir Quentin Blake – originally written for Plath’s own children, Frieda and Nicholas.

But despite her eye for beauty and quiet capacity for whimsy, Plath never exorcised the demons that haunted her formative years. In another diary entry, 18-year-old Plath presages the enduring open question of her life, so violently shut with her untimely, unspeakably heartbreaking death:

Oh, something is there, waiting for me. Perhaps someday the revelation will burst upon me and I will see the other side of this monumental grotesque joke. And then I’ll laugh. And then I’ll know what life is.

Learn more: Brain Pickings (https://www.brainpickings.org/tag/sylvia-plath/)

[http://thereconstructionists.org/page/4]

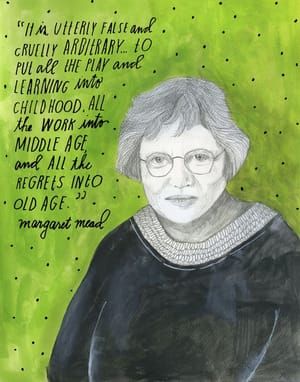

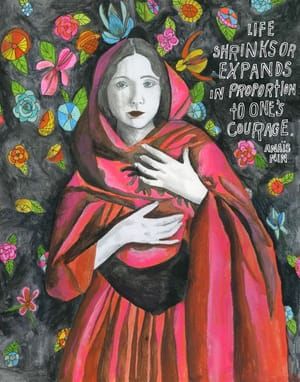

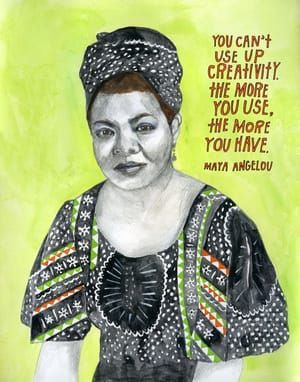

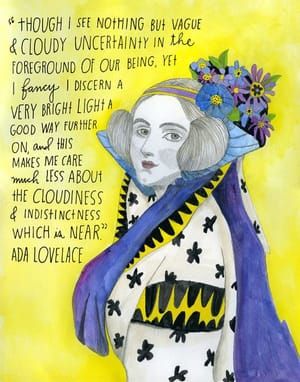

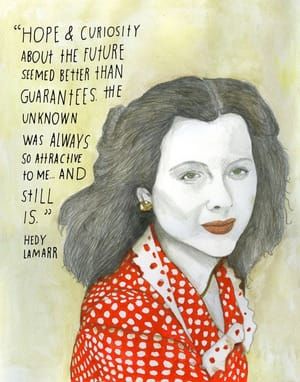

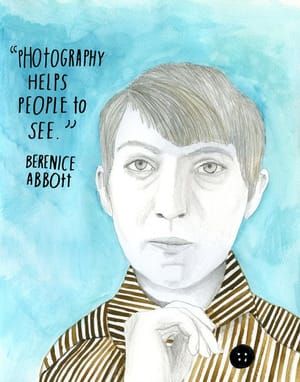

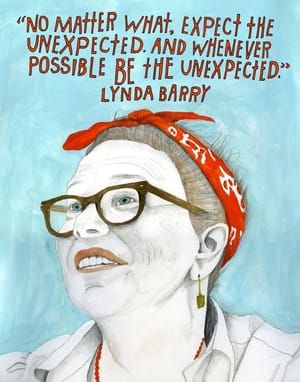

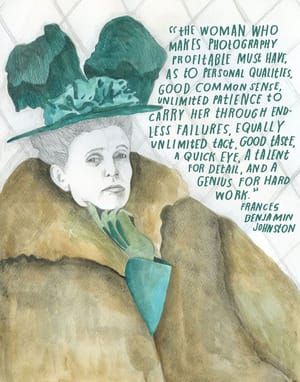

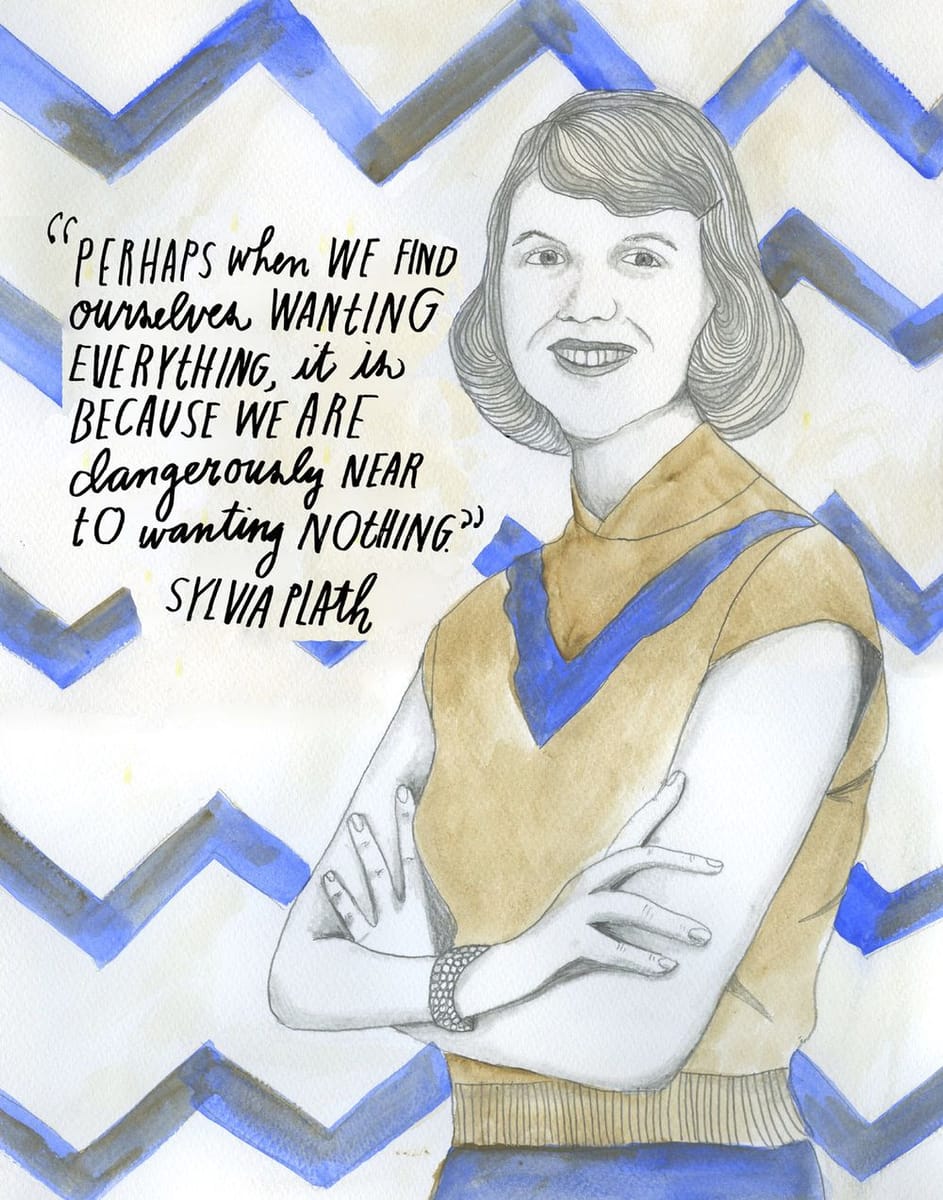

What do Buddhist artist Agnes Martin, Hollywood inventor Hedy Lamarr, and French-Cuban author Anaïs Nin have in common? Their names may not conjure popular recognition, and yet, for Lisa Congdon and Maria Popova, these women represent a particular breed of cultural trailblazer: female, under-appreciated, badass. They are “Reconstructionists,” as the writer-illustrator duo call them – and for the next year, they’ll be celebrated on a blog of the same name. Every Monday for 12 months, The Reconstructionists will debut a hand-painted illustration and short essay highlighting a woman from fields such as art, science, and literature. The subject needn’t be famous, but she will, as Popova, the creator of Brain Pickings, puts it, “have changed the way we define ourselves as a culture." We spoke with Popova, and illustrator Congdon, about the inspiration....

[http://storyboard.tumblr.com/post/41698890843/the-reconstructionists-celebrating-badass-women]

Uploaded on Jan 23, 2018 by Suzan Hamer

Lisa Congdon

artistArthur

coming soon