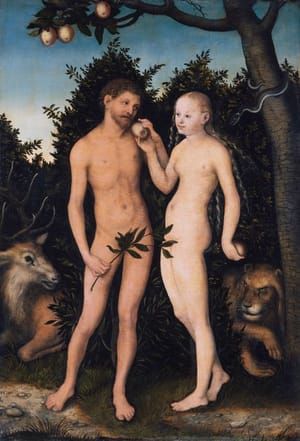

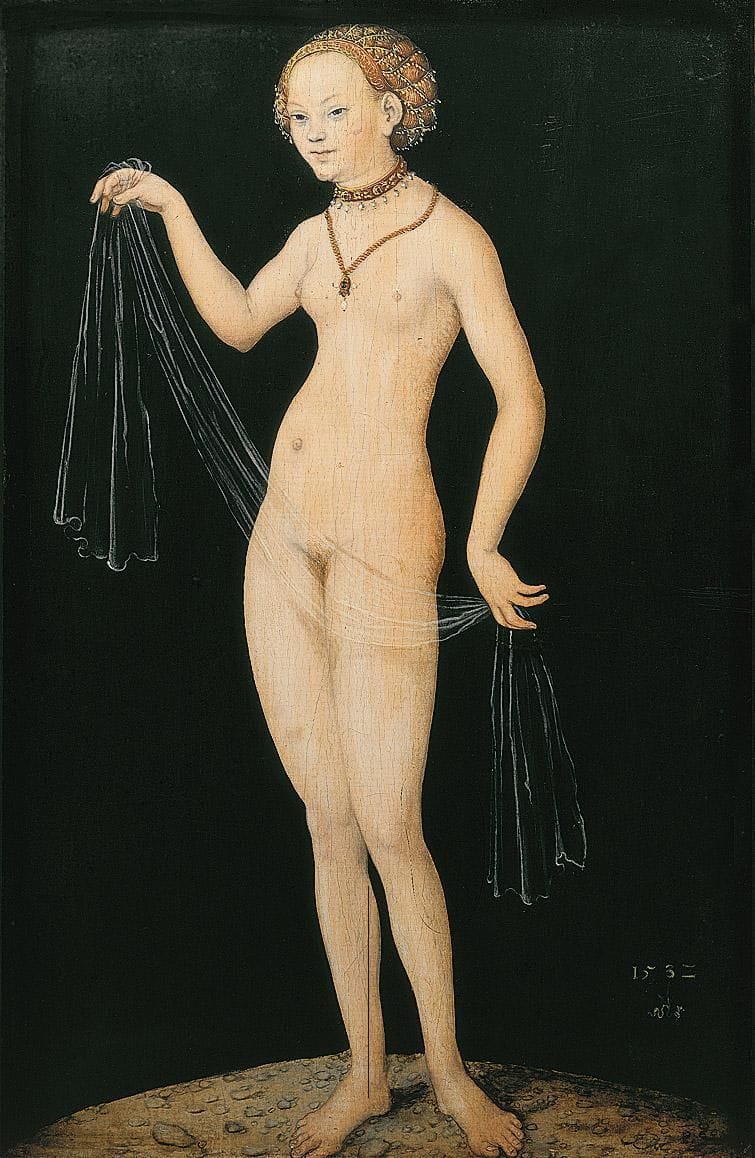

Venus, 1532

Lucas Cranach The Elder

Venus is the goddess of love and beauty. As a figure of classical mythology, she was back in vogue in the Renaissance. Lucas Cranach the Elder, a friend of Martin Luther’s, produced several depictions of her. Our little panel is special in that here the painter has demythologized Venus in a remarkable manner – she is neither accompanied by the usual Cupid, nor is there any narrative context.

At first sight, all we see is a simple nude figure, but even she raises questions. Her valuable contemporary headdress and necklaces are indications of an elevated status. A member of the aristocracy, however, would never have had herself painted naked. Venus strikes a dainty pose, her veil – so transparent as to be almost invisible – serving not least of all to facilitate the elegant movement of the arms. Also worthy of note is the manner in which Cranach handles the light.

Whereas the naked figure is bathed in light, the background behind her immediately sinks into a cosmic and inexplicable darkness. Today we are familiar with such effects from photos or stage sets. In Cranach’s time it would have been read as a surreal light atmosphere that would hardly have been associated with an earthly being. A depiction as enigmatic, seductive and intimate as this one would most likely have been executed for a private cabinet of art and curiosities.

(http://www.staedelmuseum.de/en/collection/venus-1532)

The human body is, obviously, the number one subject of European art (and of several other world arts, too). But how few of our body images involve simply the observation and recording of a body. And how many of them involve the radical alteration of a body, indeed the reconstruction of it almost from scratch....

Sometimes we take the old masters as models of sanity, when it comes to imperfect bodies and the aging process. Rubens (we say) embraces the fuller figure, the real woman. Rembrandt loves a heavy, stretched, experienced skin. Ah, how far it all is from the grim, size zero, perfecting, flesh-denying madness of our own fashion world. But if you're ever tempted to think that way, remember Lucas Cranach. You won't find a stranger or more artificial body-ideal on any modern catwalk or glossy cover.

With snake-like torso and frog-like limbs, his Venus appears against darkness. She stands on a kind of display podium, on a shallow rounded foreground of earth, like the rim of the Little Prince's little planet. She poses with outright provocation. She conceals her privates with the most plainly transparent and indicative piece of veil. She plays this light, soft strip of material floatingly across her thighs. She arouses sight and touch.

But the most striking aspect of Cranach's sexual imagination is the body he makes. She is a creature of the flat picture. She is an impossible model. Cranach uses the same devices used by that fashion magazine team when it silhouetted the woman's body and then made additions and subtractions. But here the operation has a difference. It's done in reverse.

Venus is not clothed in black. She is naked and fair skinned and seen against black. Her nude body is, in a sense, fully in sight. Yet the forms of her flesh are sufficiently smoothed over that she becomes, almost, a "white" silhouette. She has a body whose internal modulations are suppressed, and her anatomy is to be deduced principally from what her outer edges convey.

Cranach makes free with those edges. He pares out his goddess's form into a taut, slinky profile. But try to think how such a figure would be sculpted, or if it could be. It can't be imagined into solidity. This is a body that can only exist on the flat.

Yet the effect is stranger still. "White" silhouette can't be contrived as black silhouette can. Venus's internal flesh cannot be entirely vanished away, without it looking bizarre. Her breasts and tummy and muscles have a faintly rounded presence. On the other hand, they cannot be made consistent with the weird and essentially flat body that's implied by her outer edges. A contradiction arises between her contour and her flesh.

It gives a queasy feeling. The figure is as flat and sharp as a piece of snipped out paper. The body within this shape is as formless as beaten egg. Like soft cake-mix in a tin cookie-cutter, this flesh can offer no resistance to the hard, sinuous contour that Cranach binds it in.

But it's the object of erotic art to dream impossible dreams, to propose physical sensations you could never come across in reality. Cranach's Venus is a landmark of sexual fantasy. It must be someone's idea of fun.

(http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/art/features/great-works-venus-1532-lucas-cranach-the-elder-1643538.html)

A young nude woman stands in a slightly contraposto pose within a semi-circular shaped area of sandy ground strewn with stones. She is set against a deep black completely unstructured background, similar to the neutral backdrops employed for portraits. Her supporting leg is straight, her left leg only minimally angled, her feet are slightly apart and are turned outwards. The weight of her body rests on the small of her back due to the slight turn of her rear end; her head, which is inclined to the right, is stretched forward. In comparison with the solid straight stance her figure describes an S-curve. The barely suggested curve in the central axis prepares for the graceful play of arms and hands either side. The nude beauty holds her arms at an angle and has raised the right one so that the hand grasping the veil is at the same height as her shoulders. Her left arm is only slightly angled and the hand is more obviously bent back, two fingers hold the veil. The gesticulation is motivated by this and as such does not appear too artificial: the central part of the veil falls like a festoon in soft curves between her hands, while the ends fall vertically down the sides. The sheer textile appears to be on the one hand almost transparent and does not conceal the woman's hips and vulva; on the other hand the raised part of the folds and the hem appear as delicate white high-lights, which describe calligraphic-like forms on the dark ground. The abundant jewellery and head attire of the woman is in certain contrast to the lack of any clothing. She wears a golden neck collar from which a multitude of pearl pendants hang, as well as a long golden chain, with a pendant set with an emerald and three pearls. Her voluminous hair is bound under a hairnet with lozenge-shaped gold threads; at the side the hair covered by the bonnet is combed behind her particularly large, but beautifully drawn ear. The beauty blinks from her angled almond shaped eyes at the viewer with a rather distant expression.

(http://lucascranach.org/DE_SMF_1125)

Uploaded on Oct 17, 2017 by Suzan Hamer

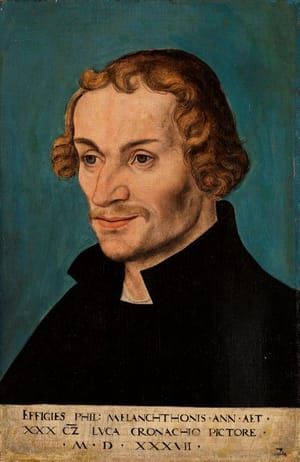

Lucas Cranach The Elder

artistArthur

Wait what?