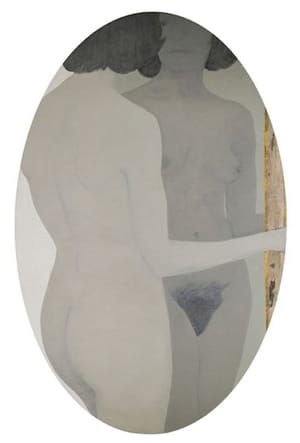

Frieze: The Porch, 1964

Marcia Marcus

Frieze: The Porch (1964) gets it title from Marcus' encounter with Byzantine art and Renaissance frescos in Florence when she studied there in 1961.

Looked at from left to right:

Jill Johnston (1929-2010), wearing a red bowler hat and holding an equally dapper cane, was born in England to an American mother and a British father; she grew up on Long Island. Having earned an MFA, Johnston became dance critic for The Village Voice in the 1960s. Her column gradually expanded into a diary of her adventures in the New York art world.

In 1971 Johnston took part in a panel discussion at Town Hall "Battle of the Sexes" that, in retrospect, was bound for notoriety. Johnston was by then an announced lesbian, her fellow panelists included Australian author Germaine Greer (The Female Eunuch) who had only just been dubbed "saucy feminist that men love" by the mainstream American press, and Norman Mailer who was - well - Norman Mailer. Johnston became an early contributor to MS. magazine after it was founded in 1972 and her best known writing is contained in the book Lesbian Nation, published in 1973. Johnston published a number of other books and was one of the more intriguing practitioners of the New Journalism but her boldness was too much for most of her male colleagues and even editors at The Village Voice expressed qualms about her activism and her outspokenness.

Barbara Forst studied at the Art Students League in New York City where she would spend most of her adult life teaching theater and producing plays off-Broadway. She died in Washington, DC in 1998.

Marcia Marcus (b. 1928, New York, NY), looking over her shoulder at the viewer and wearing a patterned cape that suggests a familiarity with Gustav Klimt's portraits, also studied at the Art Students League and also at Cooper Union where her contemporaries included Alex Katz and Lois Dodd, also figurative painters during the high tide of Abstract Expressionism. Their work shared similarities, flattening forms, strongly articulated figures and attention to pattern. All these characteristics are represented in Frieze: The Porch painted by Marcus in 1964, three years after her stay in Florence where she immersed herself Byzantine art and Renaissance fresco painting.

At the far right is a grisaille image (in black and white) that Marcus painted from a photograph of herself as a child and her father.

Although Marcia Marcus no longer paints, as Frieze: The Porch demonstrates, she deserves the attention that has been lavished on her close contemporaries and fellow downtown art luminaries: Allen Kaprow, with whom she collaborated on Happenings in the late 1950s, Red Grooms and Bob Thompson whose Delancey Street museum featured her self portraits (they received highly favorable reviews). Also, for a quarter of a century from the early 1950s until the late 1970s, Marcus spent her summers painting in a shack on the dunes near Provincetown, MA, another intensely art-centric locale. Marcus can claim an impressive list of exhibitions at such galleries as Pace, yet her name and her paintings have become invisible.

[http://thebluelantern.blogspot.com/2018/06/frieze-renaissance-art-of-marcia-marcus.html]

The very title of Frieze, alongside its linear layout and shallow depth, also alludes to antique art, most notably the sculptural frieze of the Parthenon.

...the artist’s stylistic approach lends the paintings a stilted, staged quality, as though the subjects are playing their parts in a tale. In the large-scale 1964 canvas Frieze: The Porch, for example, the three principal, larger than life-size figures—the feminist writer and Village Voice critic Jill Johnston, the Abstract Expressionist artist Barbara Forst, and Marcus herself—are arranged in a line in the immediate foreground. They don’t engage with each other but instead look out confidently, almost defiantly, at the viewer.

On the right-hand side, a painted replication of an old black and white photograph of Marcus as a little girl, accompanied by her father, is inset within the composition. Marcus uses traditional perspective here to simulate the scene captured by the camera’s lens, which contrasts starkly with the rest of the painting’s shallow depth of field and its vibrant colors and bold patterning. By representing herself with a pale gray face and wearing a cloak bedecked with a floral motif, Marcus unites these two worlds. It is unclear whether the positioning of her cloak serves to present her young self to contemporary society, or to protect her from it.

What is revolutionary here is that the subjects of the painting are now unapologetically strong women aware of the transformative parts they have chosen to play in modern life, a declaration reinforced by the staged minimalism of the formal design. Working at a time largely dominated by abstraction, Marcus stands out for looking back at the European figurative tradition. Still, by emphasizing surface and experimenting with reduction, her paintings are decidedly new.

[https://hamptonsarthub.com/2017/10/30/reviews-art-review-portraits-by-marcia-marcus-look-deeply-into-identity-at-firestone/]

...Marcus could be witty in her paintings even as she found different ways to challenge herself. Look at the understated attention she pays to cloth, pattern, and surfaces (shoes), or at the spatial complexity she achieves in “Double Portrait” (1962), “Frieze: The Porch” (1964), and “Family II” (1970) and you will be left with no doubt in your mind about how good she really is.

[https://hyperallergic.com/407992/marcia-marcus-role-play-paintings-1958-1973-eric-firestone-gallery-2017/]

Uploaded on Jun 24, 2018 by Suzan Hamer

Marcia Marcus

artistArthur

Wait what?