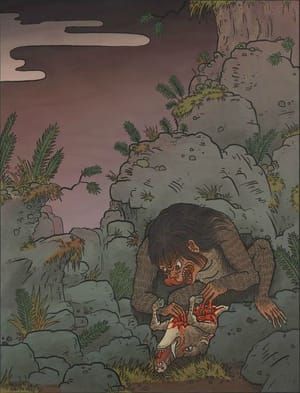

Hōsōshi, 2018

Matthew Meyer

方相氏

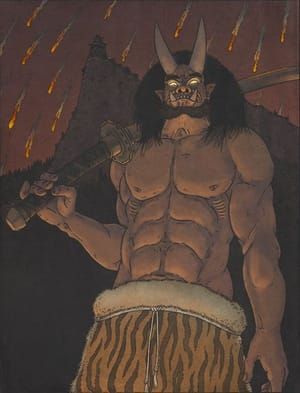

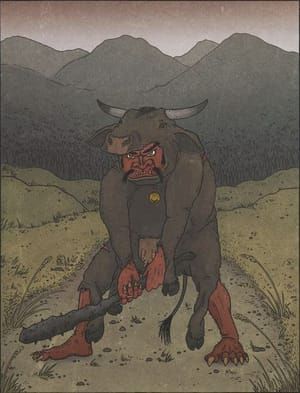

In ancient times, a hōsōshi was an official government minister and a priest in the imperial court. He wears special robes (the particular outfit varies depending on which shrine the ritual is being performed at), and carries a spear in his right hand and a shield in his left hand. The name also refers to a demon god which this priest would dress up as during yearly purification rituals. This god appears as a four-eyed oni who can see in all directions, and punishes all evil that it sees.

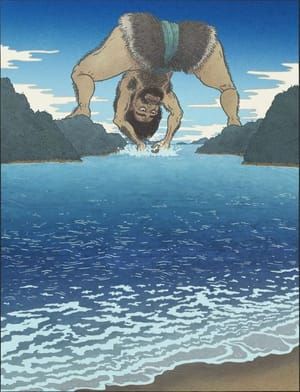

During the early Heian Period, the hōsōshi’s duties included leading coffins during state funeral processions, officiating at burial ceremonies, and driving corpse-stealing yōkai away from burial mounds. By donning the mask and costume, the hōsōshi (priest) became the hōsōshi (god) and was able to scare away evil spirits. The hōsōshi’s most famous duty was a purification ceremony called tsuina.

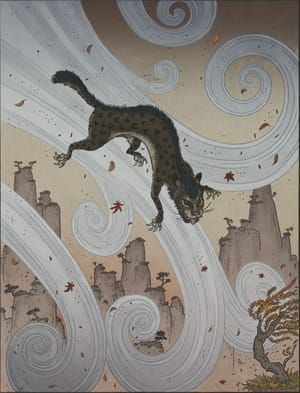

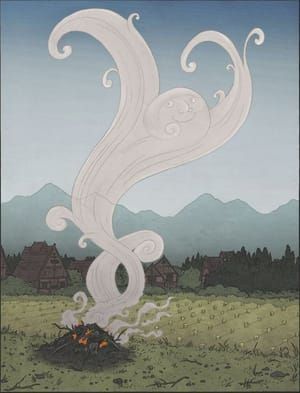

Tsuina was performed annually on Ōmisoka—the last day of the year—at shrines and government buildings (such as the imperial palace). In this ritual, the hōsōshi and his servant would run around the shrine courtyard (covering “the four directions”), chanting and warding the area against oni and other evil spirits. Meanwhile, a number of attending officials would shoot arrows around the hōsōshi from the shrine or palace buildings, symbolically defending the area against evil spirits. Other observers would play small hand drums with ritualistic cleansing significance.

Hōsō was a concept related to divination, the four directions, and the magical barriers between the human world and the spirit world. It dealt with creating and maintaining these boundaries and barriers. It including things like planting trees or placing stones in the four corners of an area, or utilizing existing features like rivers and roads, which serve as natural boundaries. By maintaining these natural boundaries, the spiritual boundaries between the worlds could also be maintained, with the ultimate goal of keeping the imperial family and other government officials safe from supernatural harm.

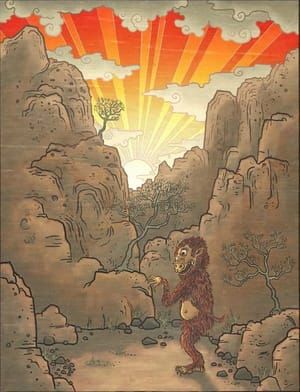

The concept originated in ancient Chinese folk religion, where it is called fangxiang. The fangxiangshi wore a four eyed mask and a bear skin, and acted as a sort of exorcist. Chinese folk religion eventually became mixed with Buddhism and Taoism, and made its way to Japan. The Japanese hōsōshi’s rituals and costume were derived from this folk belief.

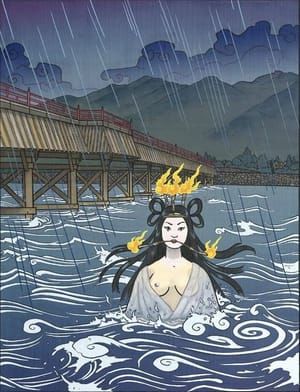

Over time, the Japanese version evolved further away from its Chinese roots. The hōsōshi came to be seen not as a god which keeps oni away, but as an oni itself. Rather than exorcising evil spirits, the hōsōshi became an evil spirit, and it was the imperial officials who chased away and exorcised the hōsōshi (thus symbolically chasing all evil spirits away). This may have been due to changing perceptions during the Heian period about the concept of ritual purity. The hōsōshi, who was associated with funerals and dead bodies, came to be viewed as unclean. It would be inappropriate for such a creature to be on the same “side” as the imperial household, so it became the target of the ritual instead of the officiator.

While the governmental position of hōsōshi no longer exists today, some shrines still perform annual tsuina rituals involving the hōsōshi. The celebration of Setsubun, in which beans are thrown at people wearing oni masks, is also derived from this ancient ritual.

Matthew Meyer

artistArthur

coming soon