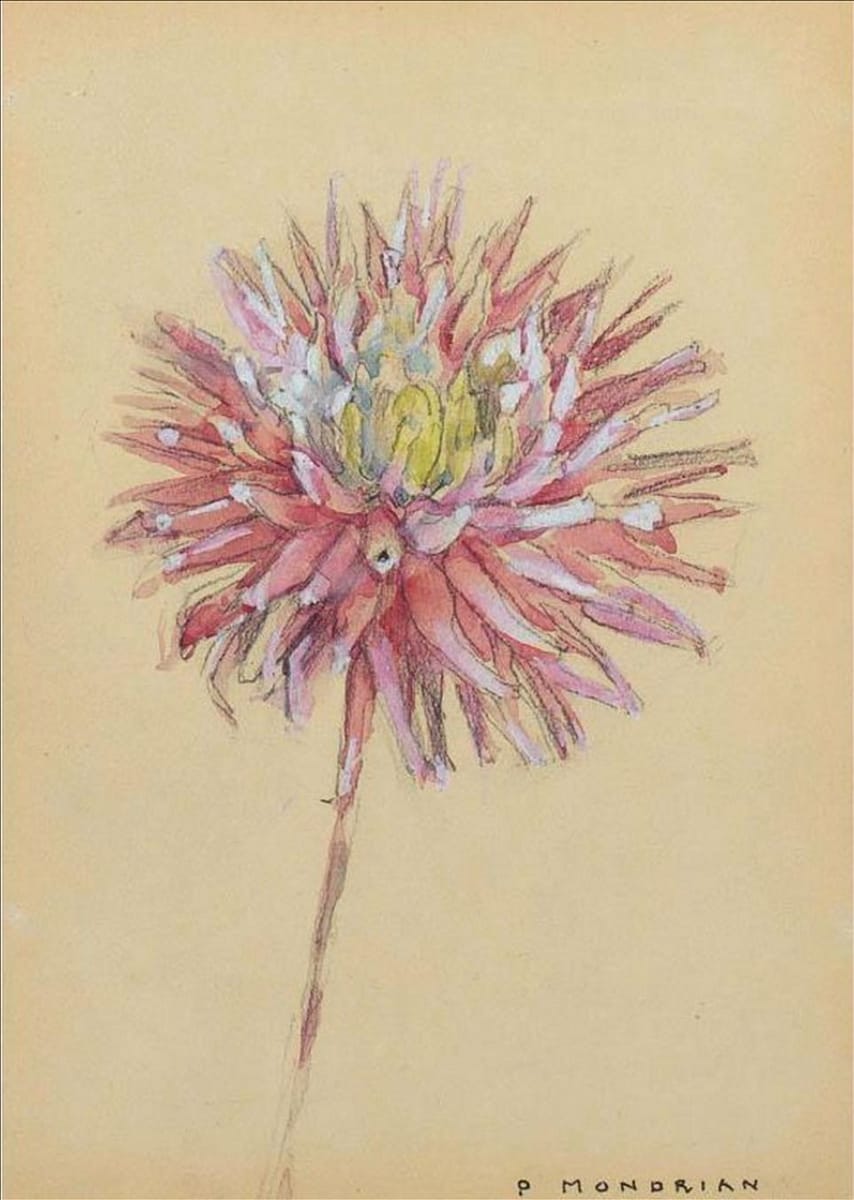

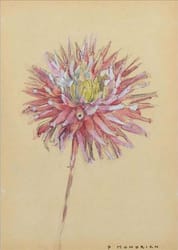

Dahlia

Piet Mondrian

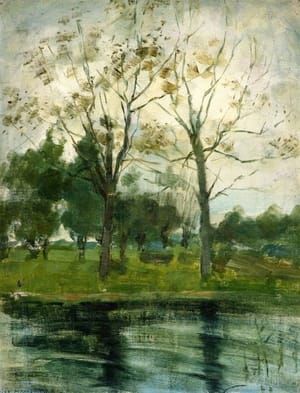

For more than a decade after graduating from art school in 1897, Piet Mondrian created naturalistic drawings and paintings that reflect a succession of stylistic influences including academic realism, Dutch Impressionism, and Symbolism. During this period and intermittently until the mid-1920s Mondrian created more than a hundred pictures of flowers. Reflecting years later on his attraction to the subject, he wrote, “I enjoyed painting flowers, not bouquets, but a single flower at a time, in order that I might better express its plastic structure.”

(https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/2999)

The Flowers That Show Mondrian Had a Softer, More Intimate Side

By MICHAEL BRENSON

Published: March 29, 1991

Forty-seven years after Piet Mondrian's death, we are finally getting an exhibition devoted solely to his flowers, those spare, sometimes quivering images that expose many sides of the artist in whose abstract grids nature seems both distilled and stilled.

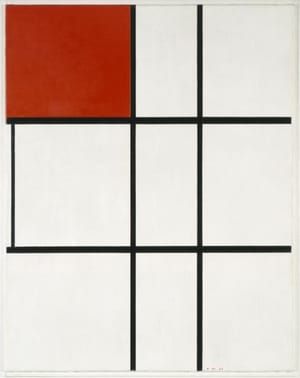

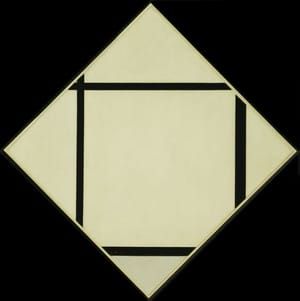

From the 37 works in "Mondrian Flowers in American Collections," at the Sidney Janis Gallery, it is apparent that Mondrian drew and painted flowers most of his life. It is also apparent that the kind of uncompromising geometric abstraction of which he remains perhaps the high priest was not enough to satisfy his artistic needs. Although he did make images of flowers for money, he clearly loved making them, and he clearly found in flowers a way of expressing an experience of suffering and solitude that is well concealed within the scaffolding and walls of his pictorial architecture.

The scholarly problems posed by Mondrian's flowers (there are, according to the gallery, around 150 in all) can be suggested by the many differences in dating between this show and the just-published book "Mondrian: Flowers" (Harry N. Abrams). Most of the flower works are undated. Two works dated 1906 and 1907 by Mondrian himself have been placed after 1920 in the show on the recommendation of Robert P. Welsh and Joop Joosten, two scholars preparing a Mondrian catalogue raisonne. If indeed Mondrian felt he had to assign later images of flowers to the earlier, figurative stage of his career, what does that say about the repressiveness of the once-inspiring abstract orthodoxy he helped construct and about his reputation as an artist who was always his own man?

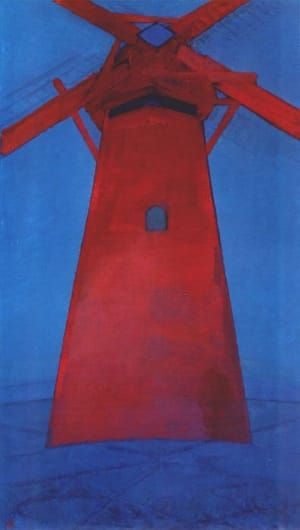

Some of Mondrian's flowers, like his gladioluses, are outgoing; some, like his sunflower, which seems caught halfway between sunlight and darkness, are strong and firm. In his "Red Amaryllis With Blue Background," the red and blue-green flower, which seems to have sprouted all at once from a wine bottle filled with water, is triumphant. The two watercolors of a single amaryllis stem -- each forming a cross with a heart of light -- have the feel of altarpieces.

Most of the flowers are delicate, with stems suspended in space amid thin color, often pale blue. In some of the images of chrysanthemums, big flowers in ripe, healthy bloom barely disturb the surface of the paper. Ripeness is celebrated yet in danger. Particularly in the chrysanthemums, Mondrian could be almost botanical in his exploration of structure and yet ever a Symbolist in his susceptibility to mood and dream.

Although no Mondrian in this show has the dramatic melancholy of the well-known 1908 "Dying Chrysanthemum," with its white skull-head comforted by a dark, pillow-soft, wall-like strip of color, a number of the works suggest pathos. One charcoal "Amaryllis" is like a crucifixion with the head of a slumped Christ. One chrysanthemum resembles a skull. In the center of another is a hint of a trapped face.

Why did Mondrian paint flowers most of his life?

For one thing, they can hold the kinds of contradictory meanings that he concentrated in his abstract paintings. They can be proud or fragile, or both. Their blooming and wilting can embody youth and age. Alone in space, they can communicate a confident or despairing isolation.

Many of the flowers seem like portraits, even self portraits. In "Mondrian: Flowers," the poet David Shapiro (who, with the book's picture editor, Christopher Sweet, collaborated on the show) makes the wonderful observation that the flowers "are the real nudes in the oeuvre of Mondrian." But it is hard to know if they are female nudes (in their delicacy and discretion) or male nudes (the emphasis is very much on the head), or nudes in which traditional distinctions between male and female are overcome.

These are very much the works of an artist who needed nature but was also uneasy with it. They are the works of someone who needed, at least on occasion, to make drawings or paintings of a soft, precarious, almost liquid reality. They are also the works of an artist whose formidable abstract achievement could accommodate conceptually but not emotionally his many sides.

(http://www.nytimes.com/1991/03/29/arts/review-art-the-flowers-that-show-mondrian-had-a-softer-more-intimate-side.html)

Uploaded on Jul 7, 2017 by Suzan Hamer