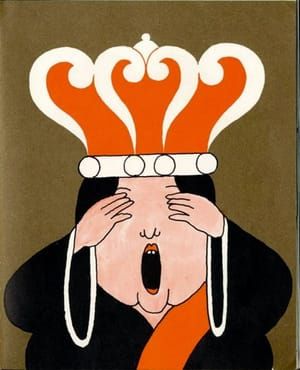

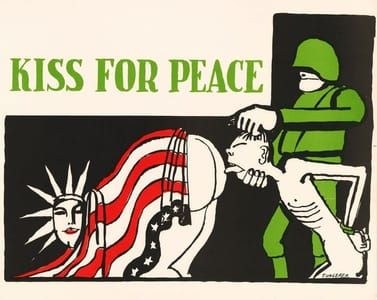

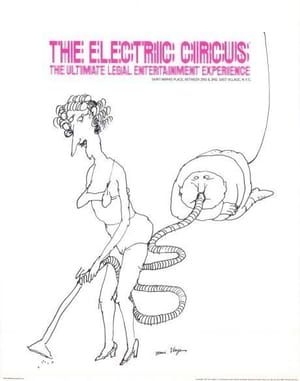

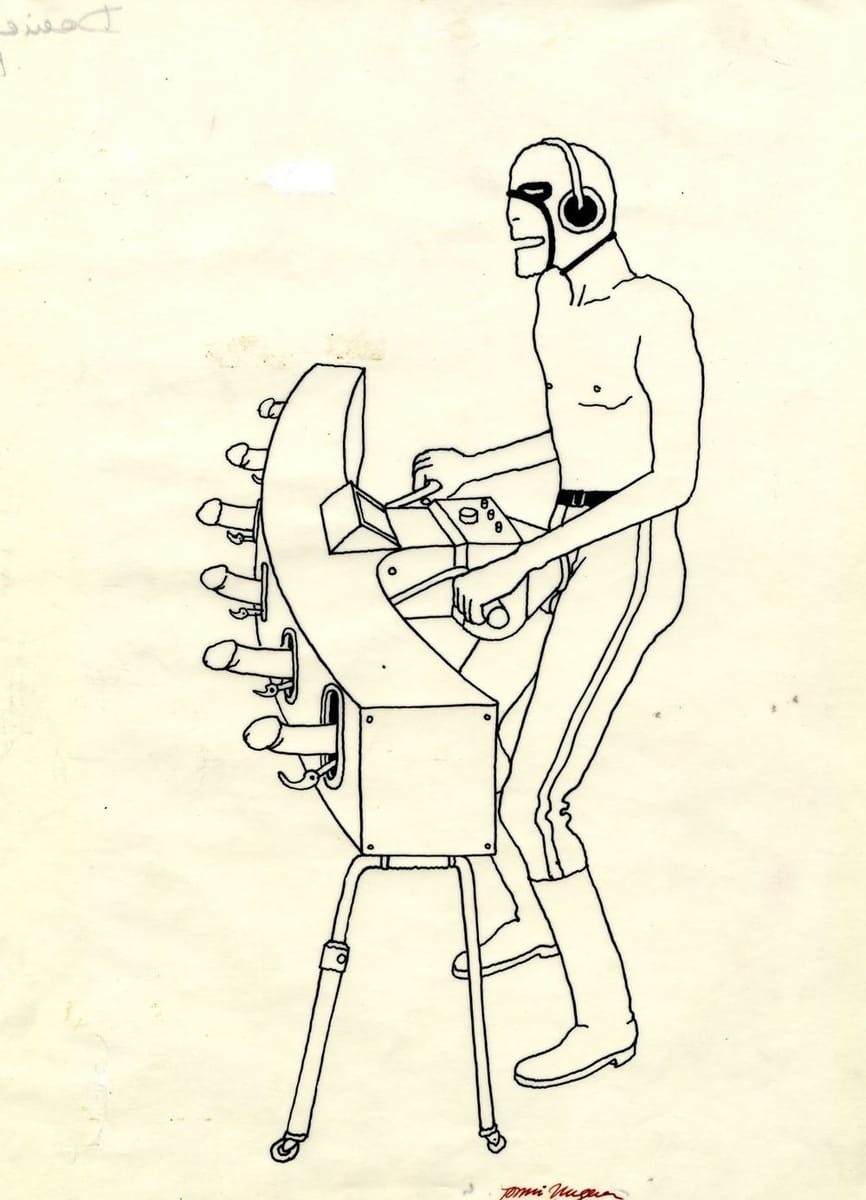

Drawing for Fornicon, 1969

Tomi Ungerer

Drawing for Fornicon, first pubished by Rhinoceros, New York). Collection: Musée Tomi Ungerer/Centre international de l’Illustration, Strasbourg. © Tomi Ungerer/Diogenes Verlag AG, Zürich.

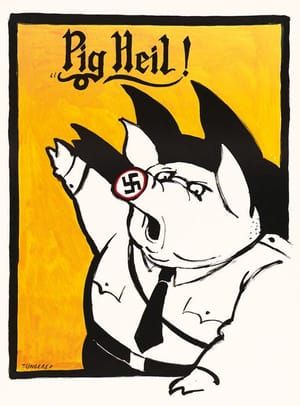

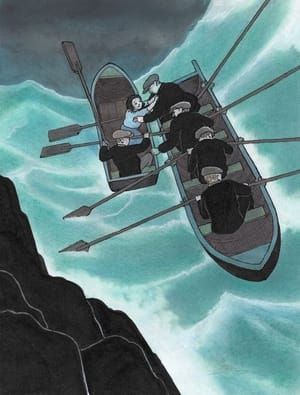

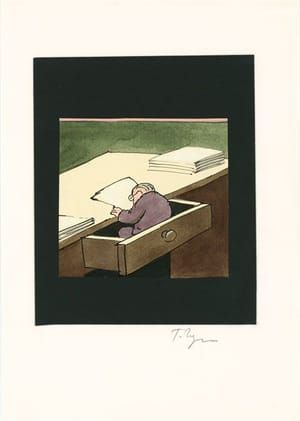

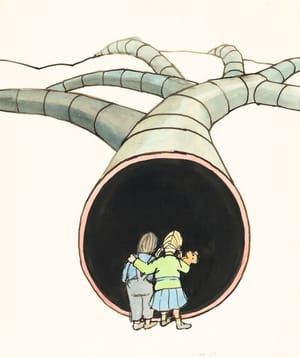

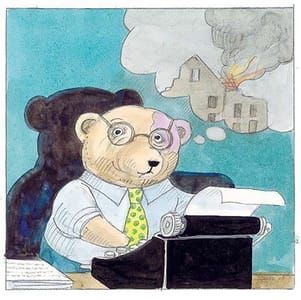

I can't fully describe the way I felt looking through the diverse, wily, brutal, and tender graphic work of this artist, except to say that my skin chilled. His hand is one of complete freedom as well as control: his humorous depictions of animals feel more human than people beside you; the elegance of the renderings of bodies and politics in Babylon and in The Underground Sketchbook seduce and invade your mind; Fornicon titilates while admonishing us and our machines; and, then there are the children's books which bestow respect on children—those who need not be coddled by the un-realities of life. Ungerer himself and his work can be flirtatious, unflinching, and ruthless in satire; his drawings always lead you on a journey that is equal parts magic yet stinks of the real....

NF I am fascinated by your images of sex, especially in Fornicon. Can you speak about your depictions of sexuality, women, and power?

TU In Fornicon, I was showing the clinical aspect of lovemaking nowadays, which is being mechanized. I was struck at the time—it was the ’60s—by how in America one book came out after the other about how to do it. So I did The Joy of Frogs, which is a satire. It’s the Kama Sutra of Frogs, showing all the different positions—as if people didn’t have enough imagination for how to do it. The Fornicon was just an extension of the same thing—do people need gadgets and instruments? It was a rebellion against a mechanization of our lives, not only of sex. We live in a world that’s completely ruled by machines. I don’t have a computer. I don’t have a cell phone. I believe in my freedom. I don’t want to be tied up by everything that is imposed upon me.

The drawings in Fornicon are medical. If you want to see some of my erotic works, look at the big album that is called Totempole, for instance. These drawings are drawn from life and they are, for me, erotic. I met this girl and I asked her what her fantasies were and she said she would like to be my slave. So, okay, that’s one game and I must say I really enjoyed it....

NF Tell me what it was like for you in the ’60s when there was such a backlash to your erotic work.

TU Around ’68, ’69. Strangely, you’d have thought that it would have been the opposite, that the blooming ‘60s would have opened—and they did open—people’s minds. But then one must also realize that the drugs had come in, too. That’s not at all my territory. Out of the blue—I think it was because of the Fornicon—there was an official notice proclaiming that all my books would be banned from American libraries, including the children’s books. That was a bit much. I still have a hard time understanding it.

(http://bombmagazine.org/article/2359112/tomi-ungerer)

Observed without the sheen of controversy, his erotic work is full of nuance: Fornicon has a fluorescent-lit quality, and steady black lines imagine men and women equipped with bizarre sex machines, like rickety, salivating superheroes. In contrast, Totempole, also using sadomasichism’s external devices and scenarios, expresses inwardness through the sketchy, hesitant line of specificity.

(https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2015/01/30/all-in-one-an-interview-with-tomi-ungerer/)

Black Power/White Power, with its Kama Sutra suggestion of simultaneous fellatio, has an undeniable sexual undercurrent, but Ungerer also addressed the sexual revolution head-on, assimilating the fluid line and stark patterning of Aubrey Beardsley in wildly phallocratic drawings of baroque pleasure devices and mechanical means of penetration. Published as an expensive folio, The Fornicon, these sprightly images—a literal, if perverse, expression of the desire to make love rather than war—provoked a strong negative reaction, effectively suspending Ungerer’s career as a children’s book artist (his works, he says, were banned from libraries) and precipitating his departure from New York, first for rural Nova Scotia and then for rural Ireland, where he showed a new interest in landscapes and domestic scenes. Before he left, however, Ungerer produced a suite of drawings depicting a young woman, usually alone, contorted in a variety of bondage positions that, more inquiry than assertion, are arguably the most accomplished and tender of his career. (Had Ungerer done the poster for The Night Porter, Liliana Cavani’s much reviled S&M love story might have had a far different reception.)

(http://www.nybooks.com/daily/2015/02/05/tomi-ungerer-brash-bold-insolent/)

14 x 11 in

Uploaded on Apr 22, 2017 by Suzan Hamer

Tomi Ungerer

artistArthur

coming soon