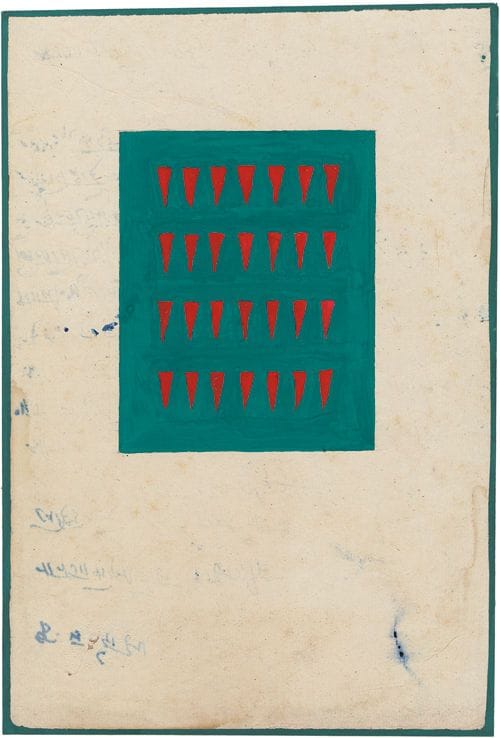

Tantric Painting, Near Udaipur, 1999

Unknown

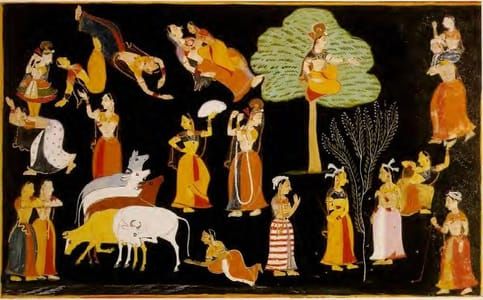

It could be a cult classic: the debut edition of Siglio Press’s Tantra Song—one of the only books to survey the elusive tradition of abstract Tantric painting from Rajasthan, India—sold out in a swift six weeks. Rendered by hand on found pieces of paper and used primarily for meditation, the works depict deities as geometric, vividly hued shapes and mark a clear departure from Tantric art’s better-known figurative styles. They also resonate uncannily with lineages of twentieth-century art—from the Bauhaus and Russian Constructivism to Minimalism—as well as with much painting today. Rarely have the ancient and the modern come together so fluidly.

For nearly three decades, the renowned French poet Franck André Jamme has collected these visual communiqués, and it hasn’t been easy: in 1985 he survived a fatal bus accident while traveling to visit Hindu tantrikas in Jaipur. In Tantra Song, Jamme assembles some of the most pulsating works he’s acquired, while unpacking his experiential knowledge of Tantra’s cosmology.

Western views of Tantra tend toward hyperbole. (The New York Times recently published an article, “Yoga and Sex Scandals: No Surprise Here,” noting, “Early in the twentieth century, the founders of modern yoga worked hard to remove the Tantric stain.”) Jamme’s book serves as a corrective to this slant and sheds significant light on the deep historical roots—and fruits—of the practice. Siglio will release a second edition of the book on April 19. Jamme and I recently discussed these anonymously made paintings, the altered states they induce, and their timeless aesthetics.

Q: It is possible to define Tantric practice?

A: Tantra is extremely difficult to explain. But it’s important to note that these small paintings come from Tantric Hinduism, beginning in the fifth or sixth century, and not Tantric Buddhism. For instance, the goddess deities are Shiva, Kali, Tara, and so on. After painting, one is to meditate with these to finally make the divinity appear. It’s an egoless practice. In Sanskrit tantra means “loom” or “weave,” but also “treatise.” The paintings date back to the handwritten Tantra treatises that have been copied over many generations, at least until the seventeenth century. At some point they evolved into this complex symbolic cosmology of signs.

Hindu Tantrism combines devotional elements with ones that may seem more mystical, such as mantras and mudras. It is really a libertarian branch of Hinduism, and often it is forbidden. So the reputation of Tantrism in India itself is not great, but in fact the families who practice this kind of meditation and make these paintings are very free.

Q: How did you find the paintings? Was it after the bus accident?

A: Unfortunately the tale of how I came to actually find these works is a very bad story—but that’s life. The first time I saw them was in little catalogue for an exhibition that was in Paris in 1970, at Le Point Cardinal Gallery. I was intrigued—they seemed so modest, compelling, and almost naturally abstract. They reminded me of poetry, and they stayed with me. Years later, I went to Nepal and stopped briefly in India, where I tried in vain to find them. In 1984 I took another trip to India but still did not find them. Finally, in 1985 I decided to focus my search just on Rajasthan. I arrived in Delhi and four or five days later departed on a bus with my wife for Jaipur. I could tell the bus driver was under a lot of stress. Perhaps he hadn’t slept in a long while. Sixty kilometers later—after we had already run into a small farmer’s cart, and the driver had to fight with the farmer—we collided head-on with a huge truck. Seven people died in the crash. I really only have fragments of memory about this and what happened immediately afterward, but after being in Jaipur General Hospital with nine fractures, I was eventually sent back to Paris in sort of a hammock.

After the bus accident I didn’t feel like speaking about it for a long time. On the one hand, it was still a bit painful, and on the other it was so odd to listen to myself tell these very strange tales. But it sweetened. After the accident happened, it took two or three trips back to India before I decided to really try to find these paintings and seek out the families who make them....

[https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2012/04/03/an-egoless-practice-tantric-art/]

Uploaded on Apr 9, 2018 by Suzan Hamer

Unknown

artistArthur

Wait what?