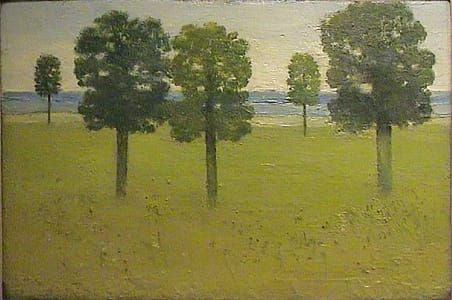

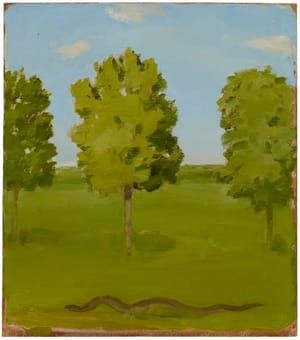

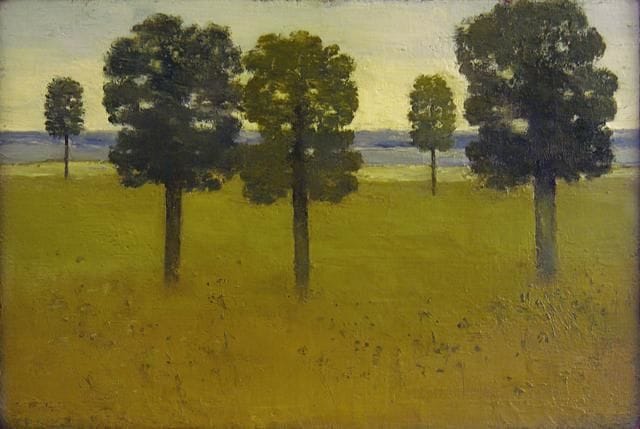

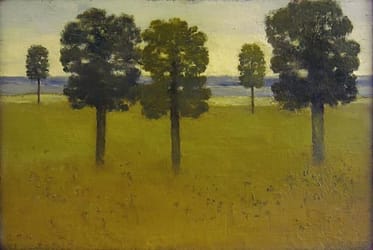

The Sea, East Hampton (also called Trees and Distant Hills, East Hampton), 1964

Albert York

Calvin Tomkins’ profile of Albert York appeared in The New Yorker in June of 1995 under the title “Artist Unknown.” Unknown, that is, to the general New York gallery-going public. And unknown, in another sense, to those painters, critics and collectors passionate about York’s work. Then as now, Davis and Langdale Company, York’s dealer since 1963—his only dealer—published these biographical facts:

BORN: Detroit, Michigan, 1928

STUDIED: Ontario College of Art Society of Arts and Crafts, Detroit

The Tomkins profile based on an interview with York—if not York’s only interview with the press it is the only one I have seen—added to these facts, but since then York has done nothing to make himself better known. He is that rarity—indeed he may be unique in New York’s art world—an artist who has no interest in publicity or celebrity and who does not care to be known as a person.

Because he has not given Davis and Langdale a new painting since 1992, their shows of his work, like the one in March 2007 in which the paintings reproduced here were exhibited, have been retrospectives. These have earned York a wider circle of devoted admirers but not a general audience. Recently, a collector gave two York paintings to the Museum of Modern Art. Slowly, his work will move out into the world, but it may never be well known and the reasons for this are instructive.

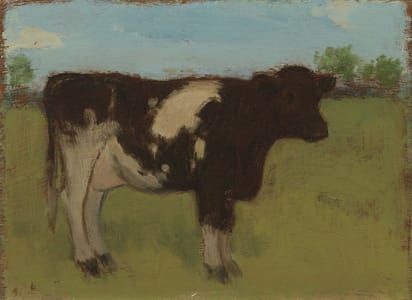

York’s paintings are small—roughly the size of the standard exhibition catalogue—and this alone has placed them outside twentieth and twentyfirst century American art. York knows this. He told Tomkins, “The modern world just passes me by. I don’t notice it. I missed the train.” If the Modern does hang York’s paintings in one of their Supersize galleries where new work is displayed, for all those with eyes to see York will subtly condemn the billboard and bigger ego trips Modernism has bequeathed us. His small paintings are exactly the size they ought to be and they have presence and volume, concreteness of fact and power of imagination that too much art that is on the train, its ticket punched for stardom, lacks. And York paints beautifully. His paintings have the glow, the inner light and the look of inevitableness that real painting has, regardless of size.

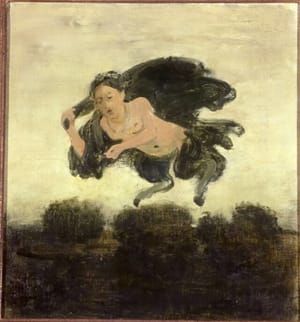

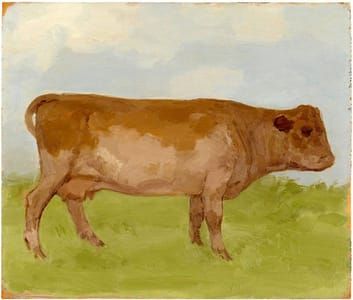

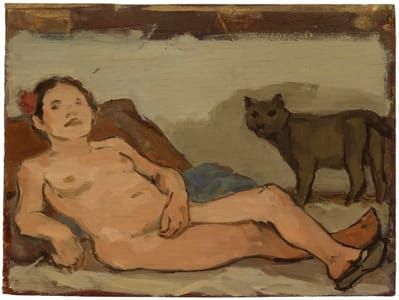

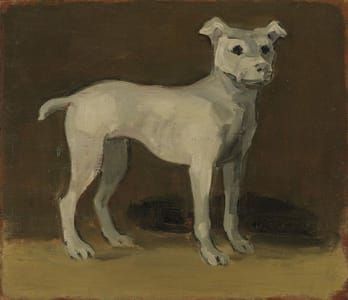

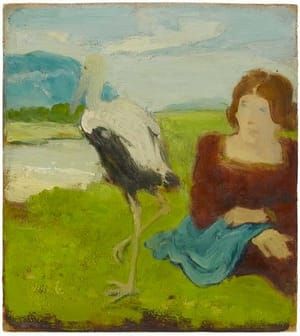

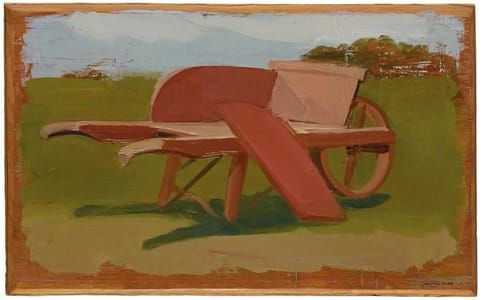

Or subject matter. It is obvious that for the most part—Flying Figure in Landscape and the wondrous Margaret Dumont-like woman posed with her dog in Woman and Dog in Moonlit Landscape—Albert York likes genre subjects. It is what he does with them, the conviction in every brushstroke, that matters. His paintings of flowers in water glasses, tin cans, glass vases and pots are the equal of Manet’s. They have a similar dash and freshness. The world has been seen for the first time, and it is thrilling. He paints a wheelbarrow in a Long Island field, at 6 7/8 x 11 3/16 inches on the smaller end of his scale, and the wheelbarrow sits like the thing it is, unlike any other, while the field recedes in the distance. So much depends upon it, like the wheelbarrow in Williams’ poem, and York’s painting is as original as “there” in the way Williams’ wheelbarrow is.

What sets York apart is clarity and originality. The clarity is on the surface and it can render the viewer speechless or, rather, wordless, his vocabulary taken away by what is so obvious it has described itself. The originality is implicit but unstated. It is there because York has an original way of seeing and of painting. It’s in the space between his trees, his variations on summer green—it is always summer in a York landscape— and in his foursquare dogs. He is pure in the sense that, in his best work, he does not care what the world outside of his painting thinks. The level of concentration is hard to achieve and hard to sustain, which may explain why York sounds so downbeat in his interview with Tomkins. He leaves the impression that he is unsatisfied with most, if not all, of his work. Perhaps, for York, talk is incapable of holding or conveying the moment like a painting does. His art is beyond words just as, so far, his life is beyond biography. This will not stop those of us who love his art from trying to speak of its mysteries or find out anything we can about the man who made them.

These are not useless or ignoble activities. York several times sent paintings to Davis and Langdale in the US mail. This remarkably casual form of transport shows faith in not only in the mail but in his dealers. He knew that they were expecting his work, that it would sell—early on for so few hundreds of dollars those who will never own Yorks must weep at the thought—and that it was understood that what mattered to him was painting. He did not care about the rest. Is this arrogance or modesty or both? Studied indifference with a hint of contempt? Just another and convenient way of keeping the world at arm’s length? After the pleasures of looking, speculation is inevitable with an artist of York’s quality and aloofness. Arrogance, the necessary amount that a serious artist must have, and modesty seem right to me, modesty to the point of anonymity, an address where York is content to reside. His art will take care of itself.

(http://www.sienese-shredder.com/2/william_corbett-albert_yorks_art.html)

Uploaded on Apr 19, 2017 by Suzan Hamer

Albert York

artistArthur

Wait what?