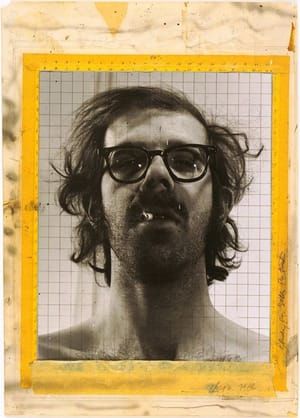

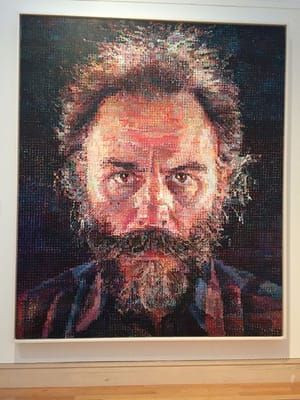

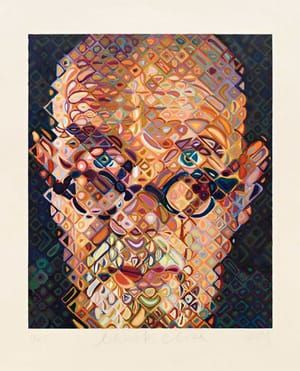

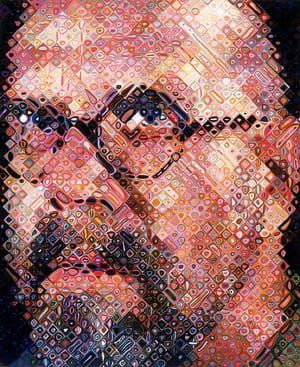

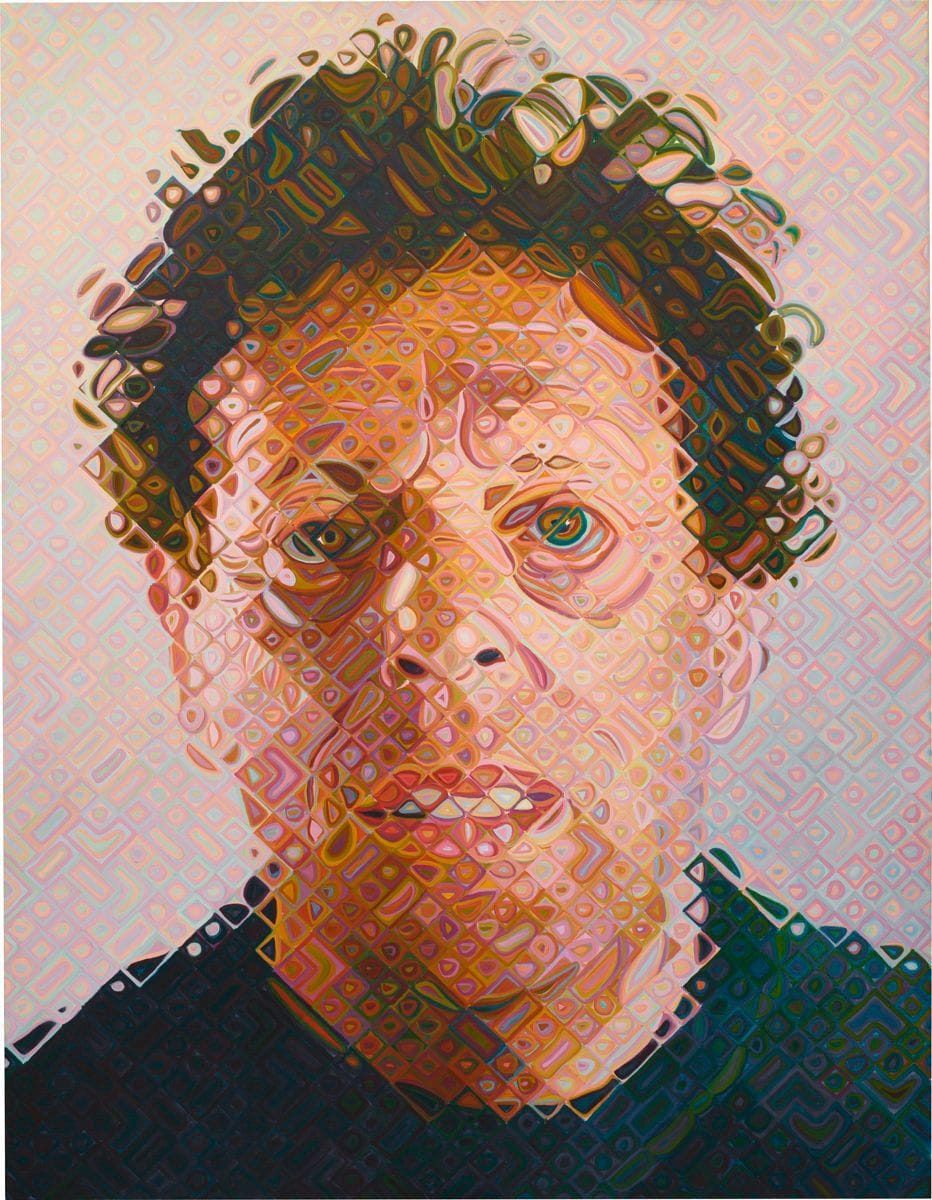

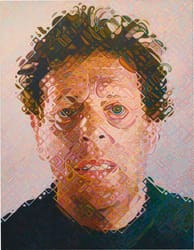

Phil

Chuck Close

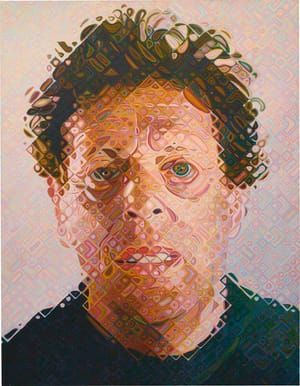

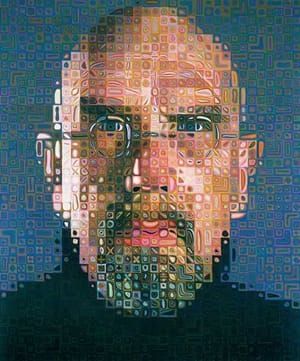

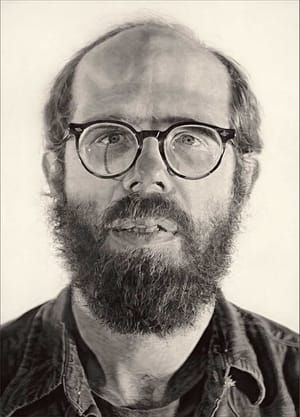

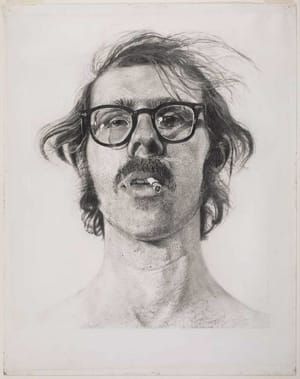

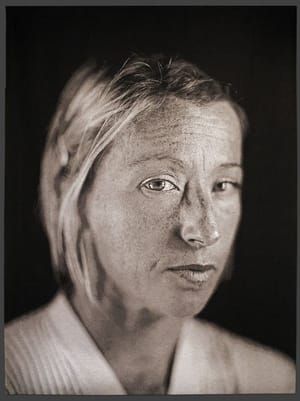

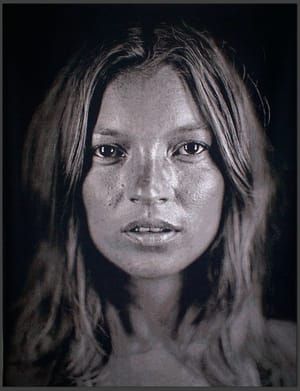

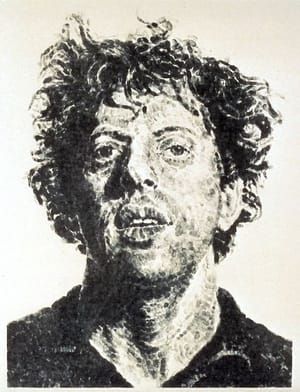

After 42 years of working from the same youthful photograph of composer Philip Glass, Chuck Close began an updated portrait of his aged friend in 2011. The meantime saw great changes in Glass's face and Close's work. Wrinkles, weight, and lines mark Glass's age, but his hair still conveys the energy of younger days. Close does not believe in adding symbolic meaning to the face, but does recognize its ability to tell us about a person's life. By this point in his career, Close began to experiment with alternative grid layouts and new ways to suggest form. Instead of using an airbrush to keep the surface of his canvas as pristine as possible, he paints an abstract arrangement of color in each square of the grid. Though our eyes combine these units to form a comprehensible image of Glass, one cannot overlook disturbing effects of such a fragmented portrait.

Like the 2011 Philip Glass, so-called veristic portraits of aged Roman men have a complicated relationship with naturalism. Although their pitted cheeks, scars, and wrinkles appear more "real" to us than the smoothed features of their idealized counterparts, the exaggerated features of these heads are just as stylized. Hyper-realism is a convention like any other, and in Roman portraiture it is used to convey authority. Grizzled visages register the battles fought, the hard work done, and the ability to persevere. The personal sacrifices one has made for improving Rome are easily recognizable, but viewers are left to wonder how much of the subject's actual appearance shows through the sitter's exaggerated imperfections. Given how we think about the aged face as a site of meaning in Roman portraiture, what kind of message does the jarring face of Close's 2011 Phil convey?

[https://www.umass.edu/umca/online_exhibitions/2015ChuckClose/verism.html]

© Chuck Close

Chuck Close

artistArthur

coming soon