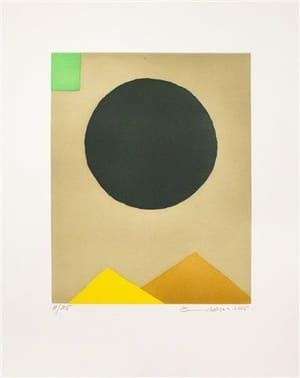

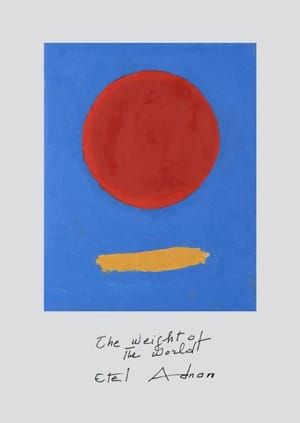

Untitled, 2010

Etel Adnan

Q: What are you trying to achieve with your paintings, and how does your chosen approach enable it?

A: I think that I am driven to paint. When you do something often enough, it becomes your identity. You don't ask why—you just do it. Like walking, for example. Once you do it, you find things to do or places to go.

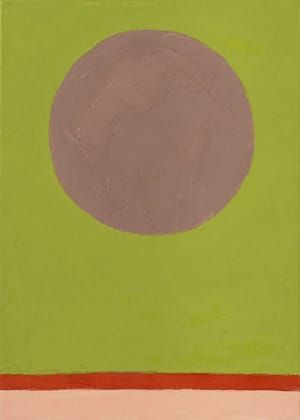

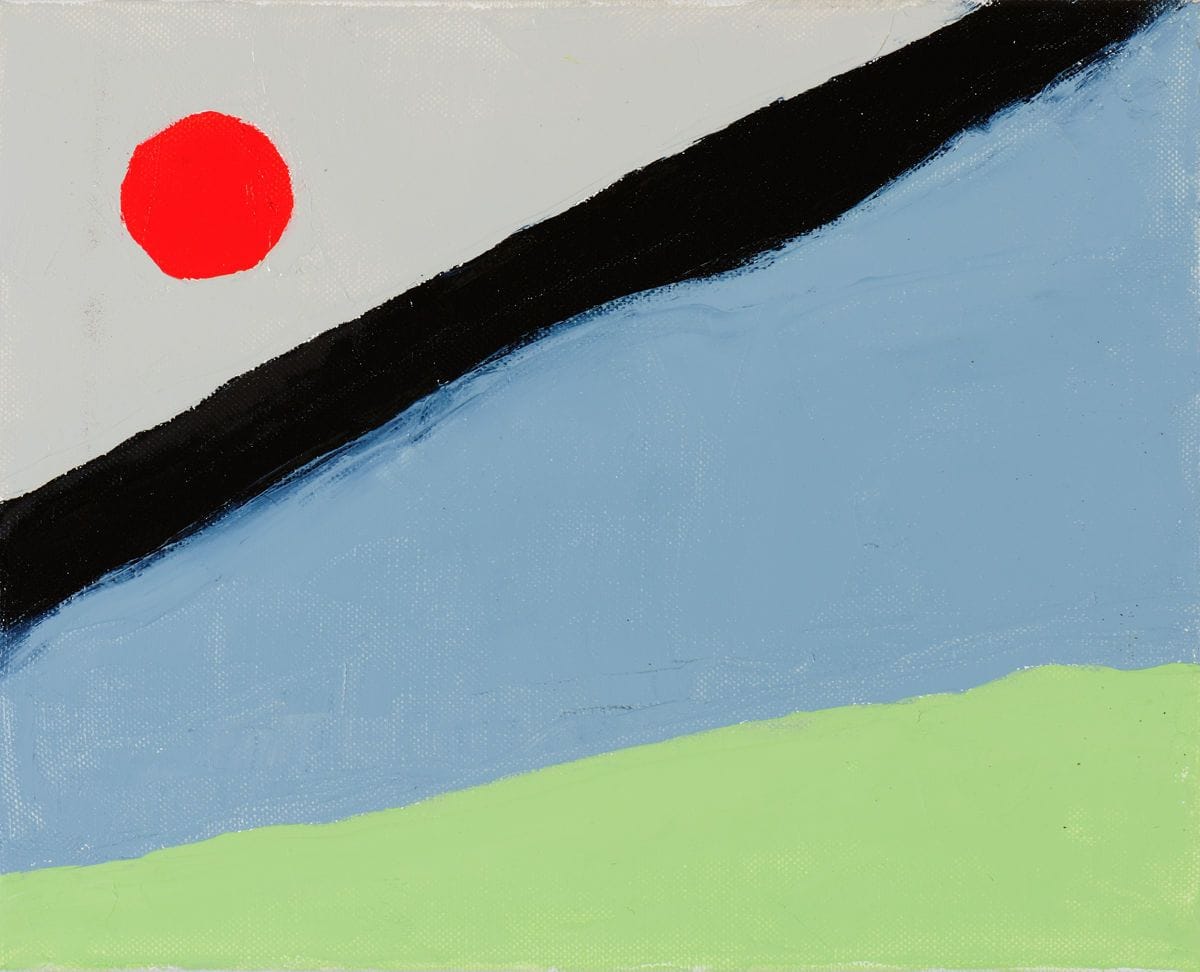

I think of my paintings as one surface after another, each calling for a new decision consistent with what's actually there. I paint in a state that is half-awake and half-asleep, deeply engrossed within my own mind. Trusting your own instincts is key. You trust that what you're doing is not just colors and shapes but the construction of something that transcends them. Painting, like music, is its own language, so you trust it and let go.

Q: What connection, if any, do you draw between your paintings and poetry? What does the age-old form of the landscape painting—abstracted as your interpretation may be—have to say to viewers in the 21st century?

A: It is probably because I am a poet and writer too that I let my paintings express the positive side of me, which relates to my profound love for nature and the world. My writings are mainly political, related to the continuous tragedies that the Arab World, from which I come, has been experiencing. My writings are also sometimes philosophical since the very functioning of the mind can be a subject for meditation.

But with canvas, paper, and colors, I feel tuned into the physical world’s power and beauty. I love nature intensely, in both its grandiose aspects and intimacies: a rose, a tree, a stream of water can give me a sense of belonging to them, which I find blissful. I love oceans and mountains, and since I spent the greatest part of my life in coastal California, I'm attached to their extraordinary beauty. Landscape paintings will always exist because it will always be natural for artists to paint their environment in a way that exalts its infinite variety and appeal.

Painting and poetry are evidently two widely different art forms. Since poetry uses words, socially shared by many, writing seems to address great numbers of people in definitive ways. Poetry is a special use of language, so it is less widely reachable. Poetry creates an aura of mystery, escaping ordinary ideas and feelings.

Paintings might seem accessible because they are visible by almost everybody but in fact can be as hermetic and mysterious as poems. They can be harder to understand. Hundreds of thousands can see an art exhibition and very few really "get it." In my case, I started writing poetry long before I started painting, so something "poetic" pervades my canvases or drawings. I can't tell how, but I hope so.

Q: In your mind, what’s the best that a work of art can do? What’s the best that a work of art has done for you?

A: We often wonder what art can do for people. I would say that art humanizes society. It brings the reminder that we are more than physical bodies. We have a spirit that needs to be fed and stimulated, with fears that need appeasement. Poetry, visual art, music, sculpture, and so on keep elevating us and opening doors to more than ourselves. They can also serve as a sort of historical monument and give us a sense of past. A society with no art is a dead society—a prison. We can extend our present notion of art by examining how anything done with care can be viewed as the beginning of an artistic instinct at work. Gardening, cooking, and sewing are seen as crafts, but they harbor an artistic desire to go further, to discover, and to procure thoughts that transcend the merely functional.

Art does the same for me. When I look at a painting I like, I feel like I am present and in dialogue with a whole world that I would otherwise be unable to define. When I paint, I feel like I am part of something bigger than myself, in communication with all those who did more or less the same thing, and part of a community within ordinary society.

(Interview continues at http://www.artspace.com/magazine/interviews_features/qa/etel-adnan-interview-54258)

Uploaded on Oct 18, 2017 by Suzan Hamer

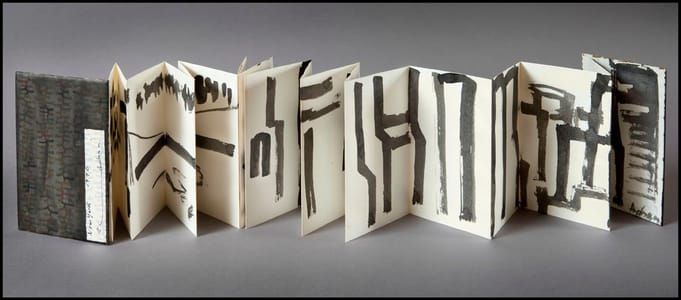

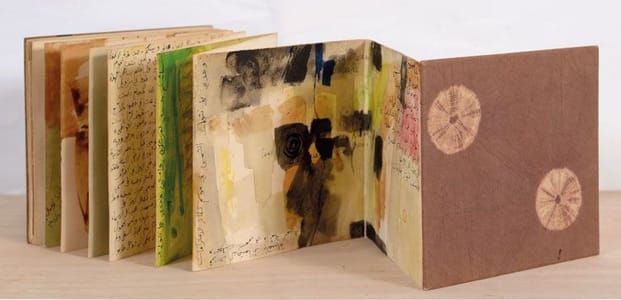

Etel Adnan

artistArthur

Wait what?