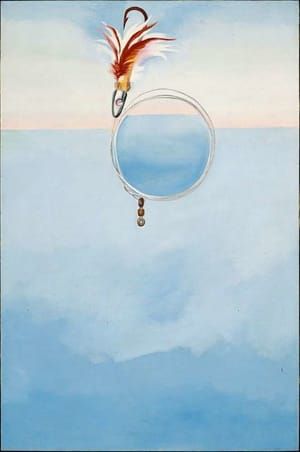

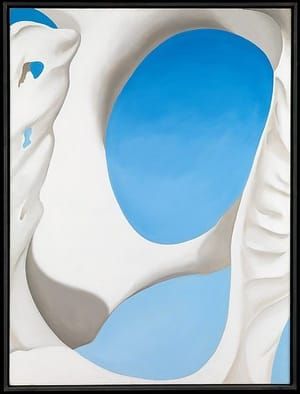

Lightning at Sea, 1922

Georgia O'Keeffe

O’Keeffe probably made “Lightning at Sea” during her stay at York Beach in southern Maine in March of 1922. It is one of a group of seven maritime paintings and pastels inspired by her visit, all of which explore sea and wave forms. While many of these works are dominated by curving organic shapes, “Lightning at Sea” is unusually angular and schematic in its composition. The hard-edged linear quality of the lightning bolt and the sun rays at its center, for example, demonstrates O’Keeffe’s awareness, of and willingness to experiment with, modernist styles that were more geometric in nature.

O’Keeffe was extraordinarily skillful in her use of pastel, as the masterful gradations of color and tone in “Lightning at Sea” make clear. She had begun to use the dry and dusty sticks of pigment and chalk in 1915, and employed it regularly over the course of her long career. She became highly adept at applying and blending pastel colors with her fingers, creating images of great depth and beauty. Her control is evident in the large bare peripheral area outside the central oval of this work. This tan field consists of raw paper only, indicating O’Keeffe’s precision in the application of the medium, which can often be messy and difficult to control.

O’Keeffe showed “Lightning at Sea” in early 1923 at New York’s Anderson Galleries as part of an ambitious exhibition titled “Alfred Stieglitz Presents One Hundred Pictures: Oils, Watercolors, Pastels, Drawings, by Georgia O’Keeffe, American.” As its title makes clear, Alfred Stieglitz, the influential photographer, art dealer, and O’Keeffe’s soon-to-be husband, organized the show and threw his considerable clout behind the work of this still comparatively-unknown artist. A contemporary reviewer quoted Stieglitz as saying, while standing in the gallery, “Women can only create babies, say the scientists, but I say they can produce art, and Georgia O’Keeffe is the proof of it.” (Helen Appleton Read, “Georgia O’Keeffe’s Show an Emotional Escape,” “Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 11, 1923, p. 2B).

The exhibition was a great success, garnering near-universal praise from the elite New York critics of the day. Many, however, expressed surprise at the idea that a woman could create significant artworks. Others labeled O’Keeffe’s compositions as direct expressions of female sexuality, excluding all other interpretations. A typical reviewer claimed that the artist’s picture of a cow eating an apple symbolized “the cosmic urge of the eternal feminine.” (Henry Tyrrell, “Art Observatory,” “The [New York] World,” February 4, 1923, p. 9M). As a relative newcomer to the New York art world, O’Keeffe chose not to challenge the influential critics who reviewed her work directly. Only later in her career, after she had become an established painter, did she express her discomfort with these gendered readings of her images.

“Lightning at Sea” did not sell in 1923, but remained in the artist’s personal collection until 1953 when William H. Lane purchased it for his important collection of American modernist artworks.

Heather Hole

[http://www.mfa.org/collections/object/lightning-at-sea-35100]

© 1922 Georgia O'Keeffe

Georgia O'Keeffe

artistArthur

coming soon