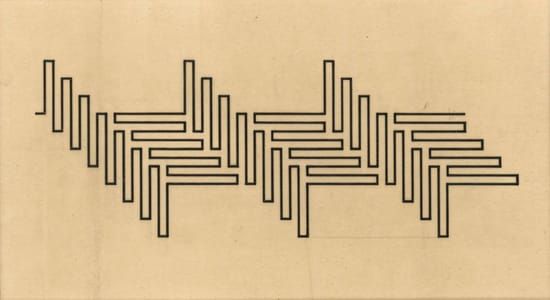

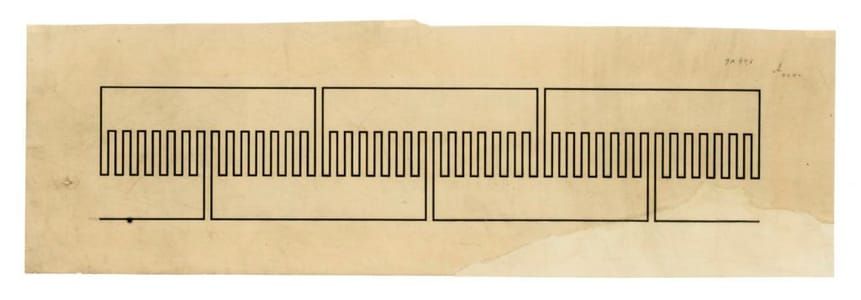

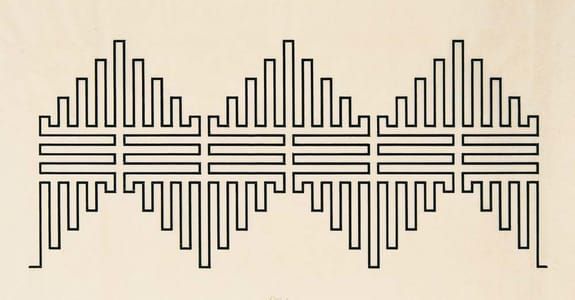

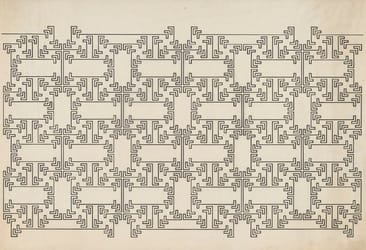

F7, 1926

Wacław Szpakowski

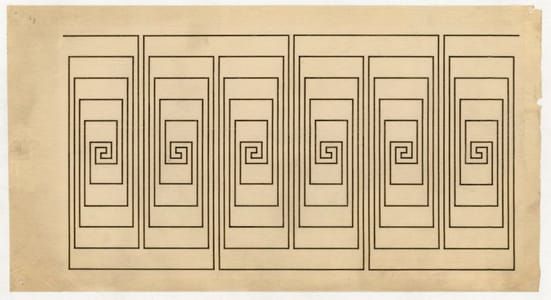

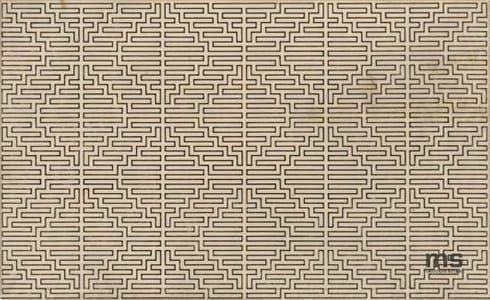

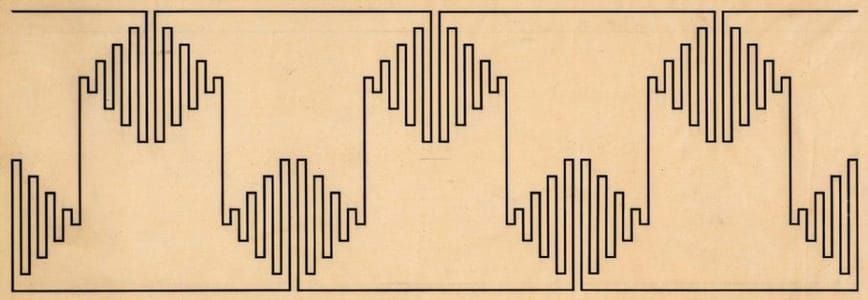

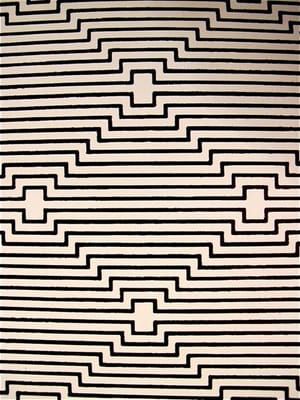

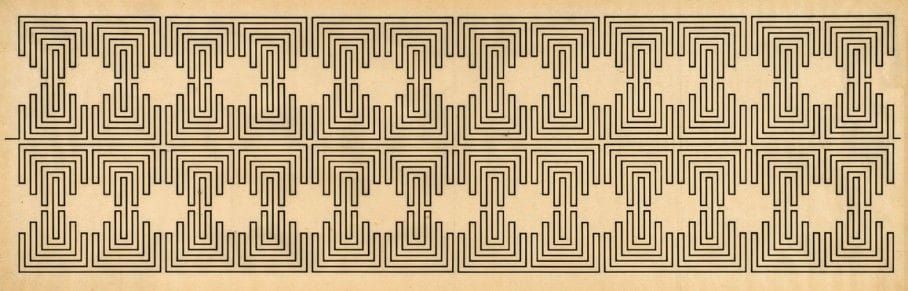

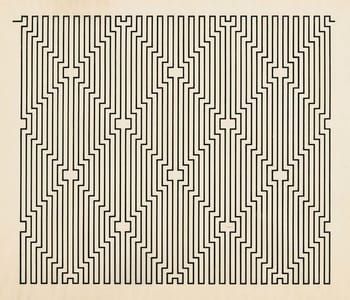

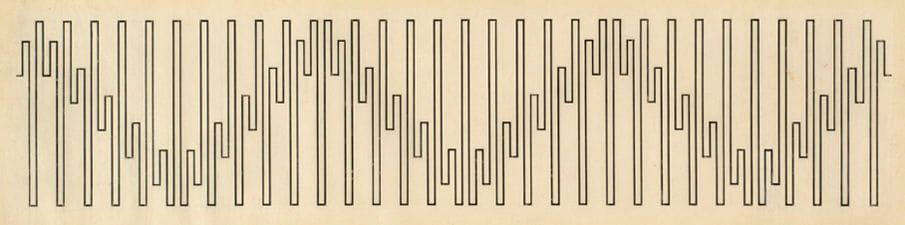

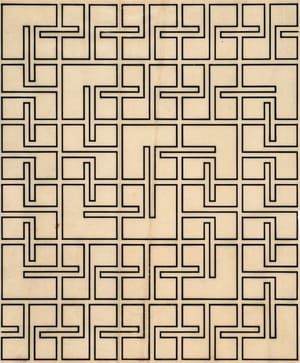

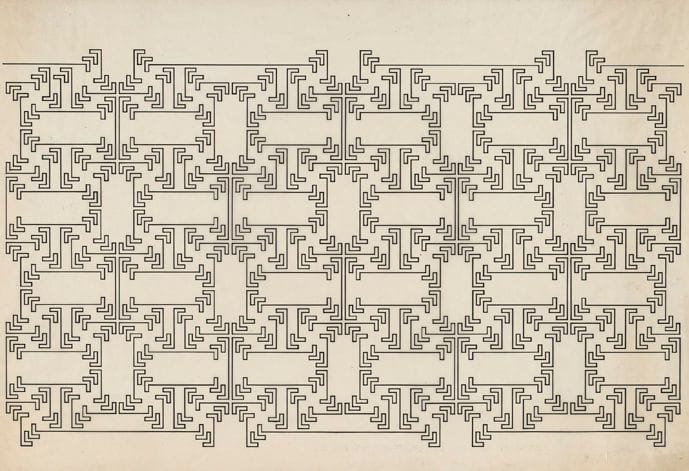

Waclaw Szpakowski deserves a permanent place in the history of contemporary art. The drawings by this pioneer of abstract art, made of a single, unbroken line create beautiful, rhythmical and quasi-labyrinth forms with a visual and temporal character.

[http://www.wroclaw2016.pl/waclaw-szpakowski-18831973.-rhythmical-lines]

Working in isolation, Wacław Szpakowski made mazelike drawings from single, continuous lines.

When he was 85, Wacław Szpakowski wrote a treatise for a lifetime project that no one had known about. Titled “Rhythmical Lines,” it describes a series of labyrinthine geometrical abstractions, each one produced from a single continuous line. He’d begun these drawings around 1900, when he was just 17—what started as sketches he then formalized, compiled, and made ever more intricate over the course of his life. His essay is written from the contrived vantage of the third person, betraying an anxiety about his own artistic validity. The drawings, he explains, “were experiments with the straight line conducted not in research laboratories but produced spontaneously at various places and random moments since all that was needed to make them was a piece of paper and a pencil.” Though the kernels of his ideas came from informal notebooks, the imposing virtuosity and opaqueness of Szpakowski’s final drawings are anything but spontaneous or random. His enigmatic process—how he could draw with such supreme evenhandedness, could make his designs so pristine and yet so intricate—is hinted at only in his few visible erasure marks. One drawing reveals two lines bordering the thick final one, a possible clue that Szpakowski may have gone over each design’s path three separate times.

These works did not reach an audience until 1978, five years after Szpakowki’s death; today they’re still obscure and easily misunderstood. They’ve crept into exhibitions over the years, but mostly in the artist’s native Poland…

Though this text is aimed at an imaginary future viewer, Szpakowski could never have anticipated the particular tensions of the 21st-century gaze: our initial suspicion that the designs, for their perfection, must be computer generated; and, upon discovering that they’re not, our fetishizing his hand-drawing technique. Szpakowski took issue, in his lifetime, with the swallowed-whole way of looking that rendered his designs mere decorations, perhaps drawing on older referents like the ancient Greek meander motif or textile patterns. He insists that “a single glance would not be enough,” and that his were in fact “linear ideas,” with “inner content” accessible only to those who follow the line with their eyes on its journey from left to right: a process not unlike reading.

[complete article at https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2017/02/15/rhythmical-lines/]

Szpakowski played the violin rather well and liked to think of his "rhythmic lines" as music. It is true that if one follows one of his infinite lines from beginning to end, as he wanted the viewer to do, one does experience up-down-forward-backward rhythms that resemble melodies. The geometrical structures created in this way during a period of over 50 years, from 199o to 1954, were treated at the same time as sound recordings, almost as scores of musical pieces, discovered in nature. Cycles of sketches, invariably drawn with a single line, never crossing, referring to both visual, sound and psychological sphere of human experience, became Szpakowski's method of describing the world.

[Looking at Numbers Door Tom Johnson,Franck Jedrzejewski; found on Google Books]

26 x 39 in

Uploaded on Dec 15, 2017 by Suzan Hamer

Wacław Szpakowski

artistArthur

Wait what?