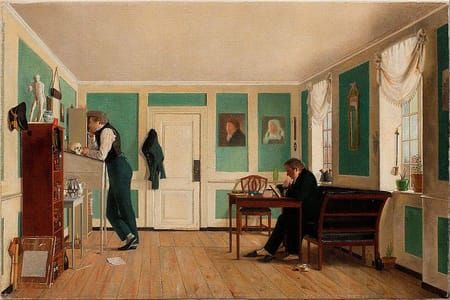

The Raffenberg Family, 1830

Wilhelm Bendz

In many ways this is a typical bourgeois family portrait from the first half of the 18th century. It looks exactly how you would expect a painting of this kind to look: this was how the affluent middle classes wanted to present themselves.

It has all the trimmings of the genre: fashionable clothes, artfully arranged hair of the kind that can only be achieved by people with plenty of time on their hands and servants at their beck and call; a home suitably furnished with a piano and knitting kits – the socially approved pastimes for women - as well as with casts of ancient sculpture, art on the walls, and shining examples of closely knit, uncomplicated family relationships neatly seated (or standing) in and around the Empire-style furniture.

So all the basics are in place here for a well executed, but unsurprising example of a type of painting popular among the affluent bourgeoisie – but closer inspection of Bendz’s painting of the Raffenberg family reveals it to be infused by a keen, distinctively personal eye for the opportunities offered by the genre. It stands out from the crowd.

Bendz’s brief career hardly had time to fully hit its stride before he died at the very young age of 28, but he nevertheless succeeded in creating a surprising range of works that simultaneously reaffirmed and redefined various genres, such as the portrait – including portraits of artists, groups of artists and family portraits.

Modest in size and easily handled, this small painting of the Raffenberg family has long attracted my attention. Here at the museum it is hung high up on the wall, just above Bendz’s better-known and much larger portrait of the Waagepetersen family, dating from that same highly prolific year. So the work is easily overlooked.

I was most recently reminded of Bendz’s keen sense for deviation at the Medical Museion, where I saw his painted study of a knee with a huge tumour (painted in the same year as the Raffenberg family and possibly made at the instigation of Bendz’s brother, who was a doctor and an affiliate of The Royal Academy of Surgeons).

So who are the people in the picture? The standing woman is the mother of the seated man: Michael Raffenberg, a young barrister and councillor of state. Between them is his fiancée, Sophie Frederikke Hagerup, shown here during what may have been a slightly awkward first visit to the home of her future in-laws. The picture they are looking at – it may be a painted portrait or a drawing – is (presumably) a portrait of her future father-in-law: even though he had been dead for some years by this time he still merits a place in this family portrait.

At this point in the history of patriarchy, it would hardly have been possible to envision a family portrait without a father figure. In this case the father has died, and it is time for the son to take over his role as head of the family. The councillor’s prominently featured index finger shows the girl who’s in charge. It also transfers authority from father to son: I am like my father, and as he was, so shall I be. There should be no doubt as to the proper order of this family – and of all things in general.

Two issues in particular are of special note about Bendz’s painting. Both are so blindingly obvious that I myself hardly noticed them for a long time. One is that the main protagonist usually found in a typical family portrait is absent. The other, even more unusual feature is the fact that the picture gazed upon by the group is held in one of their hands.

I can think of a handful of paintings whose main protagonist is not present in the flesh (many more if that main protagonist is a god). A person represented in disguise or in effigy, i.e., as a picture within the picture, regardless of whether that picture is painted, engraved or carved – that is not so unusual. However, I cannot for the present recall having seen any other painting where a person is absent from a portrait, but present in a painting of which we only see the back.

Then again, there is of course the Spanish Baroque artist Diego Velazquez’s large-scale painting Las Meninas, 1656, The Prado, Madrid, where we only see the royal couple indirectly in a mirror in the background while we as spectators are looking at the back of the portrait on which the artist is working. It is unlikely that Bendz ever saw this painting (as the saying goes), but he may well have known of it, perhaps via Goya’s reproduction. Ah, well, never mind – the sense of absence in Bendz’s painting is remarkable and unusual in any case.

The other striking feature – the hand-held painting – is also quite unique. A possible parallel might be Antoine Watteau’s sublime painting L’Enseigne de Gersaint (The Shop Sign of Gersaint) (1721, Schloss Charlottenburg, Berlin): it offers a look inside an art dealership where a range of paintings are being packed up, studied, handled and presented – one of them is even seen from behind. Nevertheless, this painting is unlikely to have been a reference used by Bendz, not even as a remote source of inspiration. Bendz is somewhere else entirely. In history. In life. In society. He is telling us a completely different story.

The inclusion of the painting with its back turned out towards us informs us very clearly that the persons in this scene and the picture they look at are connected by close family ties. A scene of intimate family life is played out before our eyes – the presentable, respectable facets of family life as well as the more intimate aspects that only the inner circle knows and can access.

We see the three persons, but we do not know what they are looking at – and we barely know what they are feeling. Here, then, we face the limit for what can be represented and made visible to others. And this makes us, as spectators, aware of the special emotional ties within this family – without compromising patriarchal hierarchy. The father figure – and, hence, the family legacy – remains present as a focal point to the living, and that figure is honored as if it were a work of devotional art.

Here, Wilhelm Bendz has created a painting that points towards a model for how a painting can or should be handled. Paintings should be looked at, but at the same time they are private objects that we can touch, move around, take in, bring along and connect with. A merger of the visible and the invisible, the external and the internal.

Uploaded on by Suzan Hamer

Wilhelm Bendz

artistArthur

Wait what?