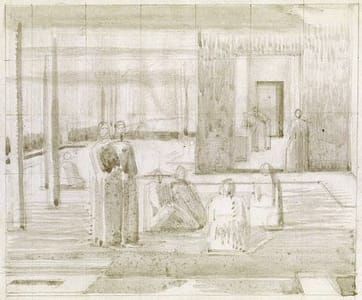

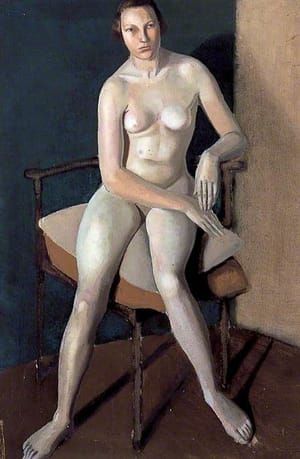

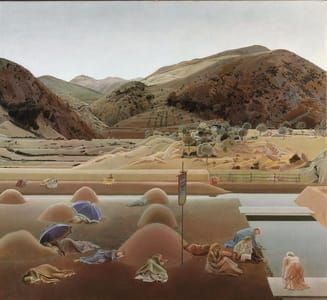

The Marriage at Cana, 1923

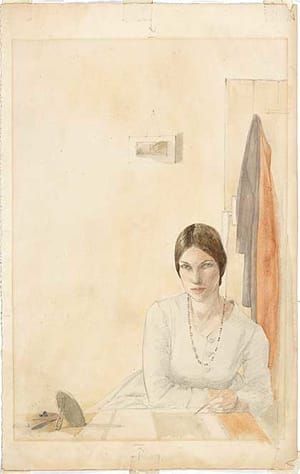

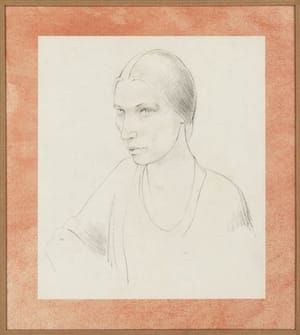

Winifred Knights

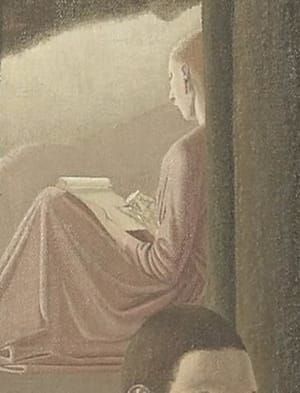

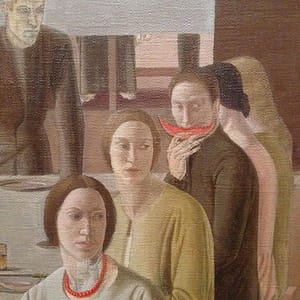

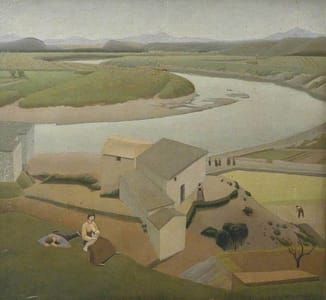

All of these skills are on triumphant display in The Marriage at Cana, a monumental account of the New Testament miracle in which Christ turns water into wine. Knights, who had long abandoned church-going, is more interested in the human rather than the sacred drama. The figure of Christ, smuggled off to one side, has no halo and the actual moment of transformation is blocked from view by the staunch buttocks of a leaning woman, modelled by Knights’ own sister. The focus of the painting instead is on the astonished faces of the guests, dining al fresco in the Villa Borghese gardens. Turning aside from their luscious pieces of watermelon, they regard the miracle with serene awe. Knights puts herself at each of the three main tables, a sly comment perhaps on the way that, during her time as the first female Prix de Rome scholar, she had become a ubiquitous celebrity in the ancient city. Sharp-eyed viewers will also spot that her fiance Arnold Mason poses with his arms defensively crossed and at a distance while, on the background table, and seated next to Knights, is Monnington, the Slade scholar whom she would soon marry. (https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/jun/25/how-painter-winifred-knights-became-britains-unknown-genius)

The pinnacle of her Italophile creations is the Marriage at Cana (1923), a complex but harmonious description of the biblical scene, in which Knights appears several times, including as a sketching artist. Slices of watermelon punctuate the muted tones with sensuous pink. A later painting featuring scenes of St Martin of Tours’ life is more luminous in colour but rather forced compositionally. (http://www.standard.co.uk/goingout/arts/winifred-knights-exhibition-review-a3265291.html)

Uploaded on Aug 18, 2016 by Suzan Hamer

Winifred Knights

artistArthur

Wait what?