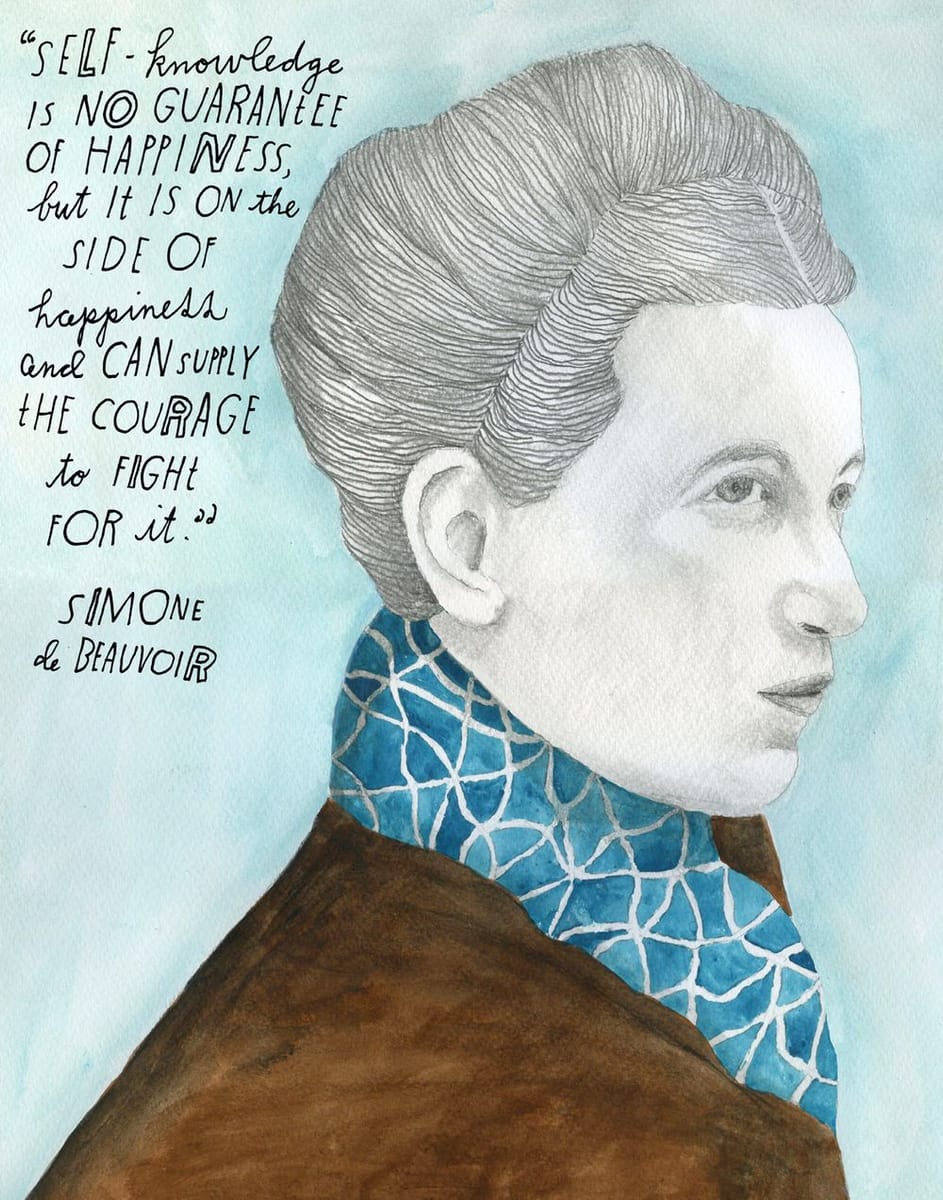

Simone de Beauvoir

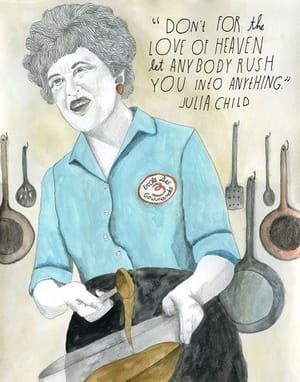

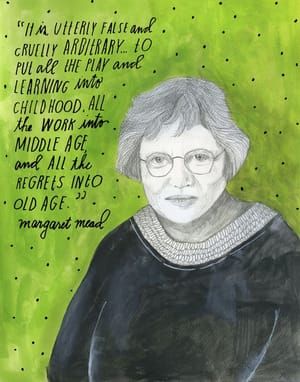

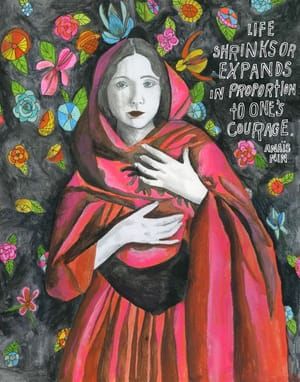

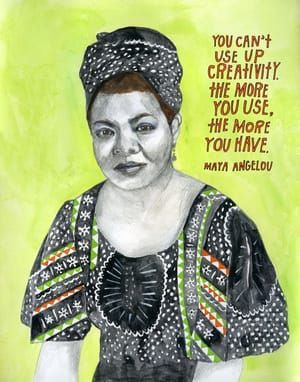

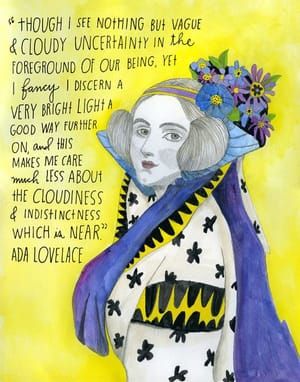

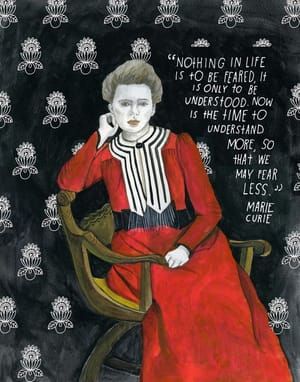

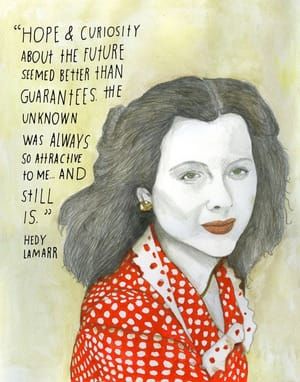

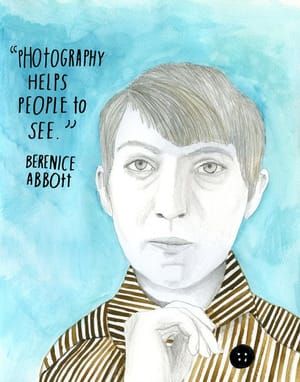

Lisa Congdon

French writer, philosopher, cultural critic, and public intellectual Simone de Beauvoir (January 9, 1908–April 14, 1986) is celebrated as the mother of contemporary feminism. Her 1949 treatise The Second Sex, a seminal account of woman’s role as an “other” in a world dominated and defined by male power, framed much of the dialogue on women’s rights and gender equality in the decades that followed, shaping the subsequent work of iconic reconstructionists like Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem.

An intellectually inclined child raised in a borderline bourgeois family, Beauvoir received early encouragement from her father and went on to pursue mathematics and philosophy after high school. In 1929, she met the odd-looking, spirited young man who would eventually become the iconic existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre as well as Beauvoir’s lifelong lover and intellectual companion. At the time of their first encounter, both were studying for the agrégation in philosophy – the high French graduate degree – and Beauvoir placed second in the entrance exam, behind Sartre, though the examination jury reportedly agreed that she was the better philosopher of the two. Only 21, she became the youngest person in history to have passed the exam.

Despite – or perhaps because of – their intense love, as evidenced by their letters, Sartre and Beauvoir maintained an open relationship for the half-century that they were together. Each had multiple affairs, but in the context of a French bourgeois society, where the practice appeared to be a mundane male prerogative, their arrangement was much more radical and norm-defiant for Beauvoir, who had a number of both male and female lovers over the years, than it was for Sartre – it became her way of reclaiming the same equality and freedom in matters of the heart and body that society had afforded to men.

In 1949, Beauvoir published The Second Sex in French – her landmark conception of feminist existentialism, which not only outlined the systematic moral evolution necessary for true gender equality but also called, in unambiguous terms, for a fundamental moral revolution.

The book was quickly translated into English and published in America under the efforts of Blanche Knopf, the wife of publisher Alfred A. Knopf. But what may at first glance appear an admirable feat was in fact a lamentable and far-reaching cultural mistake: Howard Parshley, the translator Knopf had enlisted in the task, had only basic proficiency in French and hardly any grasp of philosophy, which rendered his translation a travesty of Beauvoir’s work – much was mistranslated, resulting in damaging distortion and loss of meaning, and entire parts were cut. To make matters worse, Knopf deliberately suppressed competing translations for more than a quarter century, which made Beauvoir’s seminal treatise largely misunderstood and underappreciated in America. It wasn’t until the book’s 60th anniversary in 2009 that a complete English translation finally saw light of day, thanks to the combined efforts of translators Constance Borde and Sheila Malovany-Chevallier, who not only restored Beauvoir’s intended meaning but also salvaged a third of her original work that had been entirely cut.

Lisa Appignanesi writes in her biography of Beauvoir:

Beauvoir was a woman who was ardent for life in its full sensuous possibility. A highly trained intellectual, she was yet intensely aware of her body – which is what made her such a perceptive observer of women’s and her own condition… . If she felt her body had left her before the end, not even burial has been able to keep her indomitable spirit down.

Indeed, on April 19, 1986, more than 5,000 mourners of all ages followed Beauvoir’s funeral cortège as it traveled to her final resting place, the Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris. “Women, you owe her everything!” was the phrase that floated through the grieving crowd and echoed across the world.

Beauvoir’s legacy permeates the very fabric of modern society and has shaped our understanding of equality, but folded into it is also a subtle reminder that we, as a culture, still have a long way to go: It’s been argued – right here, right now, for instance – that Beauvoir deserves a Nobel Prize for her work, but, true to the Prize’s gender bias, she was never even nominated for one. And yet what greater contribution to global peace and justice than laying the foundation for a model of humanity in which one half is equal to, not lesser than, the other?

[http://thereconstructionists.org/]

The Reconstructionists: Celebrating Badass Women

What do Buddhist artist Agnes Martin, Hollywood inventor Hedy Lamarr, and French-Cuban author Anaïs Nin have in common? Their names may not conjure popular recognition, and yet, for Lisa Congdon and Maria Popova, these women represent a particular breed of cultural trailblazer: female, under-appreciated, badass. They are “Reconstructionists,” as the writer-illustrator duo call them – and for the next year, they’ll be celebrated on a blog of the same name. Every Monday for 12 months, The Reconstructionists will debut a hand-painted illustration and short essay highlighting a woman from fields such as art, science, and literature. The subject needn’t be famous, but she will, as Popova, the creator of Brain Pickings, puts it, “have changed the way we define ourselves as a culture." We spoke with Popova, and illustrator Congdon, about the inspiration behind their project....

[http://storyboard.tumblr.com/post/41698890843/the-reconstructionists-celebrating-badass-women]

© Lisa Congdon

Lisa Congdon

artistArthur

coming soon